감독 알레한드로 알바라도 호다르 Alejandro ALVARADO JÓDAR, 콘차 바르케로 아르테스 Concha BARQUERO ARTÉS | Spain, Portugal | 2024 | 99min | Documentary | 국제경쟁 International Competition

Resistance Reels is based on the documentary Rocío (1980) that Fernando Ruiz Vergara left, as well as his extensive notes and writings. You are picking up where Vergara left off and starting anew from the point where he had to stop. What led you to decide to create a documentary that pays tribute to Vergara and reconstructs his unfinished project?

We knew about the film Rocío by reference—the myth of an Andalusian film that was censored in the midst of democracy—but we didn’t truly discover it or Fernando until we began an academic research on the subject. Meeting Fernando was a revelation for us. We visited him in the Portuguese village where he lived, and he welcomed us into his home for several days, during which we did practically nothing but attentively listen to the stories and memories that he told us vividly and passionately. We didn’t have much in common beyond our Andalusian origins but we both felt a great connection with this man who lived in solitude yet felt fortunate for the people who had taken an interest in his work, and who still maintained a great curiosity about things. In fact, during that first encounter, Fernando tried to involve us in the last project he had in mind—a documentary about the wolfram mines of Panasqueira, near his home. We tried to help him move that film forward, but a year later, Fernando passed away. When we accessed his materials, scripts, and notes for films that had never been made—carefully preserved and generously shared by his Portuguese friends—we knew we wanted to make a film about those unfinished projects. Rocío was a great film beyond the injustice of its censorship, and we wanted to help break free from the narrative of damnation that had confined both Fernando and his work. In addition to the deep affection we had for him, which was fundamental in pushing us to make Resistance Reels, we felt politically aligned with Fernando’s projects and believed that continuing his work in the present was an act of justice and and a beautiful creative gesture, taking the baton as another generation of Andalusian filmmakers.

The names of the victims are mentioned in Vergara’s Rocío and in his notes. The cemetery that appears at the beginning of Resistance Reels, the names shown in Vergara’s film, the faces of the townspeople, the festive procession, the people gathered in the square, and their faces shouting slogans also appear in your recordings. It seems as if everyone is trying to restore those names and remember those individuals. Especially when the faces of the audience and the singers are shown, it seems like a collective portrait of the present. The people who were sacrificed under Franco’s dictatorship and those who live today continue the past and the present, and Vergara’s film continues through your film. Do you consider the names and faces of the people important? What are your thoughts on this?

The film Rocío is considered a historical source because it recovers and lists dozens of names of people who were murdered or disappeared due to fascism in the months following the coup that led to the Civil War. It also includes photographs that Fernando and his team managed to gather during a time when discussing such topics was taboo, silenced by decades of dictatorship. In this regard, the people, their names, their dignity, and their images as documentary traces were essential in Rocío as well as in Resistance Reels. Near the end of our film, two nonagenarian men appear—sons of one of the victims killed in 1936 and witnesses to the repression. When one of them, Manuel, refers to the court case against the film Rocío that ended in its censorship, he shows the camera a complete list of both victims and perpetrators, and recalls how the court insisted those events were true, emphasizing that “the people say so.” When we found the discarded footage from Rocío—which we used in Resistance Reels and previously in a short film titled Descartes (2021)—we were deeply moved by the faces of the townspeople, eerily silent in a reel where the audio had been lost. On our side, we also wanted to film other faces that represent present-day forms of resistance, yet directly tied to our history. This way, the close-up shots of Lisbon residents singing in protest against gentrification in public spaces, or the faces of the workers at the nearly defunct Panasqueira mine—people facing an uncertain future—visually connected with the ghostly imagery from the discarded scenes of Rocío.

Resistance Reels is structured in four chapters, each titled after a film. With diverse archival footage and your own video material, the themes of each chapter gradually expand. Why did you choose this structure?

Among the many projects Fernando left behind, we decided to develop—albeit tentatively—those that more clearly spoke to our present, those that allowed us to connect them with our current collective concerns. So we started with three films and an exhibition project: Otelo a Presidente, Fernando’s first attempt at filmmaking, a medium-length documentary about Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho’s 1976 presidential campaign in Portugal; Guadalquivir, a film about the main river running through Andalusia, which allowed us to talk about returning to our origins; Uma Sardinha para três, a documentary on the mine that was Fernando’s last project; and La Huelva y La Huelva, a never-realized exhibition on Fernando’s personal and political memory connected to Rocío. In fact, quite early in the writing process, we knew we wanted to revisit the unresolved issue of Rocío’s censorship and the open wound left by the crimes of Francoist repression—a wound that still persists in our country and that democracy has yet to heal in a righteous way, both for the victims and, by extension, for Spanish society as a whole. On the other hand, we wanted to make a film that was free and fluid in its form. While we did structure Resistance Reels based on those unfinished works by Fernando, our intention was to avoid any rigid template, allowing the film to evolve with a sense of life of its own.

Resistance Reels approaches the figure of Vergara from multiple angles and through various media. His personal letters and persistent notes on the project are striking, but equally fascinating is the fragmentary way in which you construct the narrative. Rather than converging all paths into a single point, you seem to layer segmented fragments. Did you choose to follow different paths to carry out Vergara’s legacy instead of following a single narrative line?

We always believed that in order to understand Fernando’s cinema and also to grasp the censorship trial that Rocío was subjected to, it was essential to come closer to his lived experience. At one point, we considered whether we should take the route of a more “pure” film essay, whatever that may mean—something focused solely on speculating about his latent and unfinished cinema, while leaving aside the man himself (or the character, if you will). But that option felt cold and overly theoretical. We didn’t want to end up making a stylistic exercise solely based on a particular idea of what cinema is or should be—especially the kind of cinema currently seen at many festivals. For us, Fernando’s life was not a complementary element but rather, to a certain extent, it explained the unfinished nature of his work. Without going any further, Fernando’s working-class background helped us understand the lack of support he found after his film was censored, and the lack of networks that ultimately plunged him into isolation.

As for the fragmentary nature, it reflects our desire to continue his legacy without falling into the temptation of sealing off his filmography definitively. From the beginning, we saw ourselves as transmitters of that legacy, something like mediums through which his work could be revived, without ever forgetting that Fernando’s filmography was interrupted for very specific reasons by very specific agents who prevented him from going too far with a process of reparation and justice that never materialized. The fragmentary form also gave us the opportunity to speak, through the film’s own form, about this interrupted life and cinematic project. Even the music that accompanies the end credits, by composer Paloma Peñarrubia, is riddled with attempts, with instrumental phrases that never quite develop and with irruptions or “interferences” from a past that continues in the present.

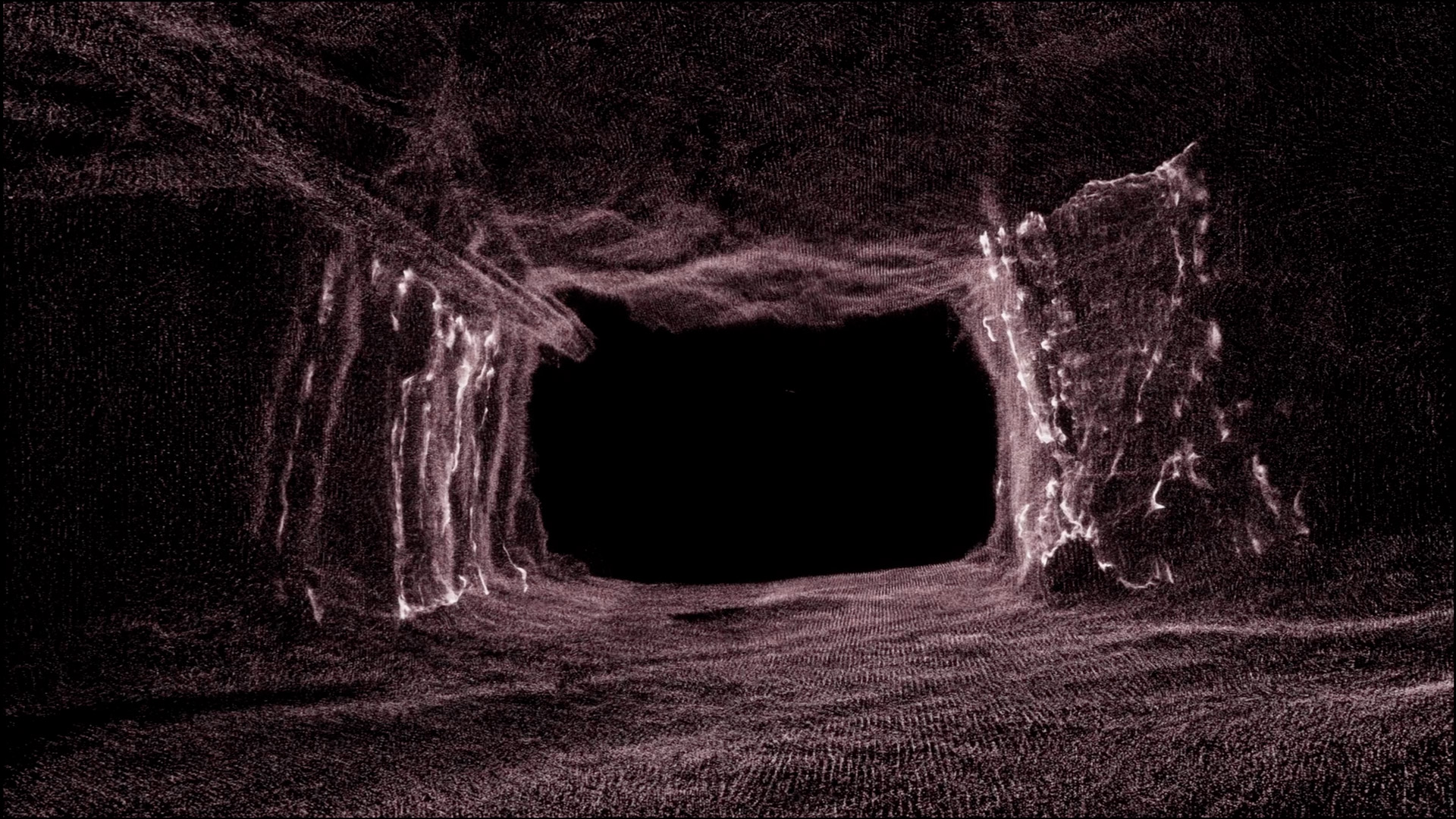

You don’t limit the film to archival footage alone, but instead experiment with various formats. Animation, in particular, has an abstract quality that contrasts with the very concrete historical facts—the miners’ workplace is depicted as if it were being swallowed by a black hole, and the miners themselves appear to disperse like dust. What led you to experiment with different formats including animation?

Wanting to speak from the present also meant that we were not trying to reconstruct Fernando’s projects, but rather to reinterpret them. Each of those projects had its own aesthetic logic for us, and these different universes entered into dialogue to shape the aesthetic of Resistance Reels. We were particularly interested in the conflict between a certain asepsis of the digital format used in 16mm—not only present in the archival materials but also in our own recordings of “memory sites”, places where the disappeared referenced in Rocío are supposedly buried. It’s also true that our perception of the digital format’s cleanliness or neutrality evolved over time, not only because it is also a convention, but also due to the contribution of the director of photography Raquel Fernández Núñez, who helped us design a versatile digital image open to unexpected and imaginative digressions. The documents and personal photographs of Fernando that we used to recover passages from his life also took on a dreamlike quality through the use of non-naturalistic color and solarization effects. This entire dimension of imagination is a strong element of the film’s concept. We asked ourselves how we could make a film that was political and beautiful, also on a visual level, and how that visuality could speak to recoverable utopias. In this sense, the animated sequence of the mine was part of the earliest drafts of Resistance Reels, and for us, it embodied the idea of imagination and fabulation. At the same time, it served as a reflection on the nature of work and bodies by decomposing the miners’ figures into point clouds, delivered to exploitation with a short life ahead of them. The animation also gave us the possibility to take an underground journey between Spain and Portugal (from the mines to the mass graves), two countries that turn their backs on each other despite sharing so much in their history and their present.

The voices reading Vergara’s notes or letters sound as if a man and a woman are conversing or singing together. In other chapters, the voices of different people also appear. What are your thoughts on the use of narration?

The soundscape is a crucial part of the film’s aesthetic. Sound acts as an expressive element that breathes new life into Fernando’s materials and establishes a bridge with the viewer, with the living act of watching. Within this universe are also our voices, which appear as a duo, complementing each other and sometimes overlapping, reading simultaneously like an echo, or as if we were both discovering in real time the surprises that Fernando’s projects had in store for us. Our voices have different functions. The most obvious is that we are a guide—albeit not entirely organized—leading the viewer through Fernando’s legacy. We thought it could be suggestive to create a sort of inventory of his unfinished projects in a somewhat cold manner, citing sources and codes for each document. But within that supposedly cold, almost forensic approach, we—those making this film, those who knew Fernando—had to emerge. The reading is full of doubts; at times we almost whisper to ourselves, telling the story to ourselves, between the intimate and the public. And we do it in Spanish and Portuguese, a language we don’t master, but for us it was important to blur the boundaries between both countries and make an Iberian, Spanish-Portuguese film, like Fernando himself. Because ultimately, the use of our voices and their occasional overlap is a way of expressing our connection with Fernando, the triangle that underlies the film at all times.

Resistance Reels seems like a kind of pilgrimage toward Vergara through various paths involving history, memory, and politics. But it is not just a pilgrimage: through your reconstruction and interpretation, you are putting into practice what you learned and felt from Vergara. What were you hoping to discover during this journey?

For us, cinema is a very important part of our lives. There is no separation between our personal world and the experiences brought about by our projects. We live it as an adventure and an opportunity to expand our experiences, as well as to experiment in the strictly cinematic sense, conceived in this way. Immersing ourselves in Fernando’s projects allowed us to take a journey back in time through the recent past of Spain and Portugal, to moments like the Carnation Revolution and the end of this period. We had the chance to meet Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, one of the icons of the revolution, and in him, we saw a reflection of Fernando, both in his deep convictions and in the failure of his project, in this political case. Resistance Reels is a film crafted in an almost artisanal way slowly-cooked, somehow dealing with many precariousness. All things considered, this gave us the opportunity to connect with the difficulties of filmmaking and making a living from it faced by a working-class filmmaker like Fernando, someone who had learned self-taught, in connection with the film cooperatives that had emerged during the revolutionary process in Portugal in the mid-1970s.

The scenes you filmed of the Guadalquivir River, the Panasqueira mine, and the sites of exhumation are beautiful and sublime—I can sense the humility and respect with which you treat your subjects. In these scenes, you use dissolves and superimpositions to create special moments. How do these techniques relate to memory, time, and contemporary political resistance?

This is basically a “montage film”, but aren’t they all? What we want to say is that the construction and the discoveries made during this phase were essential to the final result of Resistance Reels. Indeed, superimpositions and dissolves allowed us to connect places or geographic and temporal spaces that might seem distant. In other cases, these effects gave us the opportunity to highlight the documentary nature, the documentary evidence, of some of Fernando’s materials, such as his production notebook for Rocío, where he had noted down the names of the “butchers,” the perpetrators of repression, and the informants of the 1936 Almonte crimes.

The film begins in a cemetery and ends in darkness. Since starting this journey in 2010, you have conducted meticulous research over a long period, worked through an enormous amount of material, listened to testimonies, and visited the sites in person. It seems that all of this is intimately connected and has been reborn as a single documentary. In this way, the film establishes a new relationship with the audience. I can perceive multiple thematic approaches, a fragmentary structure, experimentation with media, and poetic beauty. I’d like to hear about your methodology.

For us, research is always the solid foundation of a film. Thanks to the exhaustive research, we discovered possibilities and forms of expression that ultimately “stitched together” or shaped the film. This process took a long time—both because of our artisanal way of working and the difficulty of funding a film like this—but it was key to gradually fitting the puzzle pieces into place. We see our work on Resistance Reels as an archaeological process, where we delve into different strata and make discoveries that later reveal connections between them. This idea of archaeology is also present on a visual and concrete level in the film, much of which takes place underground. The materials for Rocío are preserved underground in the Spanish Film Library; the miners work underground; and the victims are buried in mass graves. In the middle of the process, we wrote a script in our own way, which already contained structural decisions and various imagined sequences. Based on that, we continued researching and incorporating new and unexpected material, and discovering the visuality and autonomy of the images that would comprise the film. In short, we believe that if there is such a thing as our methodology, it depends on the time involved in the process, a time period that is sometimes excessive for production standards, but necessary for our experience as filmmakers.