오래된 물레방앗간 The Old Mill 감독 그레이엄 하이드 Graham HEID, 윌프레드 잭슨 Wilfred JACKSON | United States | 1937 | 9min | Animation | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU

English text below

동물이 인간의 언어를 어조, 온도, 목소리 높낮이가 아니라 문자 그대로 이해할 수 있다면, 영화감독들이 주로 사용하는 많은 표현들이 이들에게 공포나 불안감을 안길 것이다. 예를 들어 영화를 ‘찍다(shooting)’와 피사체를 ‘포착하다(capturing)’라는 표현은 (카메라로) 무장한 인간이 먹이를 쫓는 사냥의 언어를 직접적으로 모방한 것이다. 영화와 동물의 관계는 길고 풍부한 역사 속에서 이러한 ‘사냥’의 개념에 고정되어 있었다. 동물은 쫓기고, 잡히며, 동영상 이미지 형태로 박제되어 ‘보존’되었다. 사실 영화 역시 한 사람과 카메라가 한 동물을 향하면서 시작되었다고도 말할 수 있다. 그 사람은 에드워드 머이브리지, 그가 찍은 최초의 동물은 말이다. 결과적으로 이러한 관계가 영화 역사 전반을 통해 동물을 특정한 과학적, 미학적, 서사적 목적을 위해 포획된 대상으로 취급해 오는 데 일조하였다.

올해 전주에서 소개하는 〈오래된 물레방앗간〉 〈분열된 세계〉 〈네 번〉은 각각 제작된 시기와 국적이 다른 영화들로, 동물을 대하는 감독의 대안적인 입장을 제시한다. 동물과 자연에 대한 각 문화권의 뚜렷한 태도 차이를 반영하고 있는 이 영화들을 창작된 시대와 시공간의 산물로만 단순화할 수는 없다. 대신 이 세 편의 영화는 동물 주체성과 그들에 대한 인간의 이해 부족, 영화적 표현의 한계에 대해 탐구적이고 진보적으로 접근함으로써 영화사를 관통한다. 인기 애니메이션, 종교적 우화, 아트하우스 슬로우 시네마(Slow Cinema)에 이르기까지, 다양한 장르를 선보이는 이 세 편의 영화는 동물이 여전히 주로 서사적 장치, 즉 영화를 끌고 나가면서 관객을 몰입시키는 힘든 노동을 해야 하는 일종의 (무보수) 배우로서 기능하는 여러 방식에 대해서도 이야기한다.

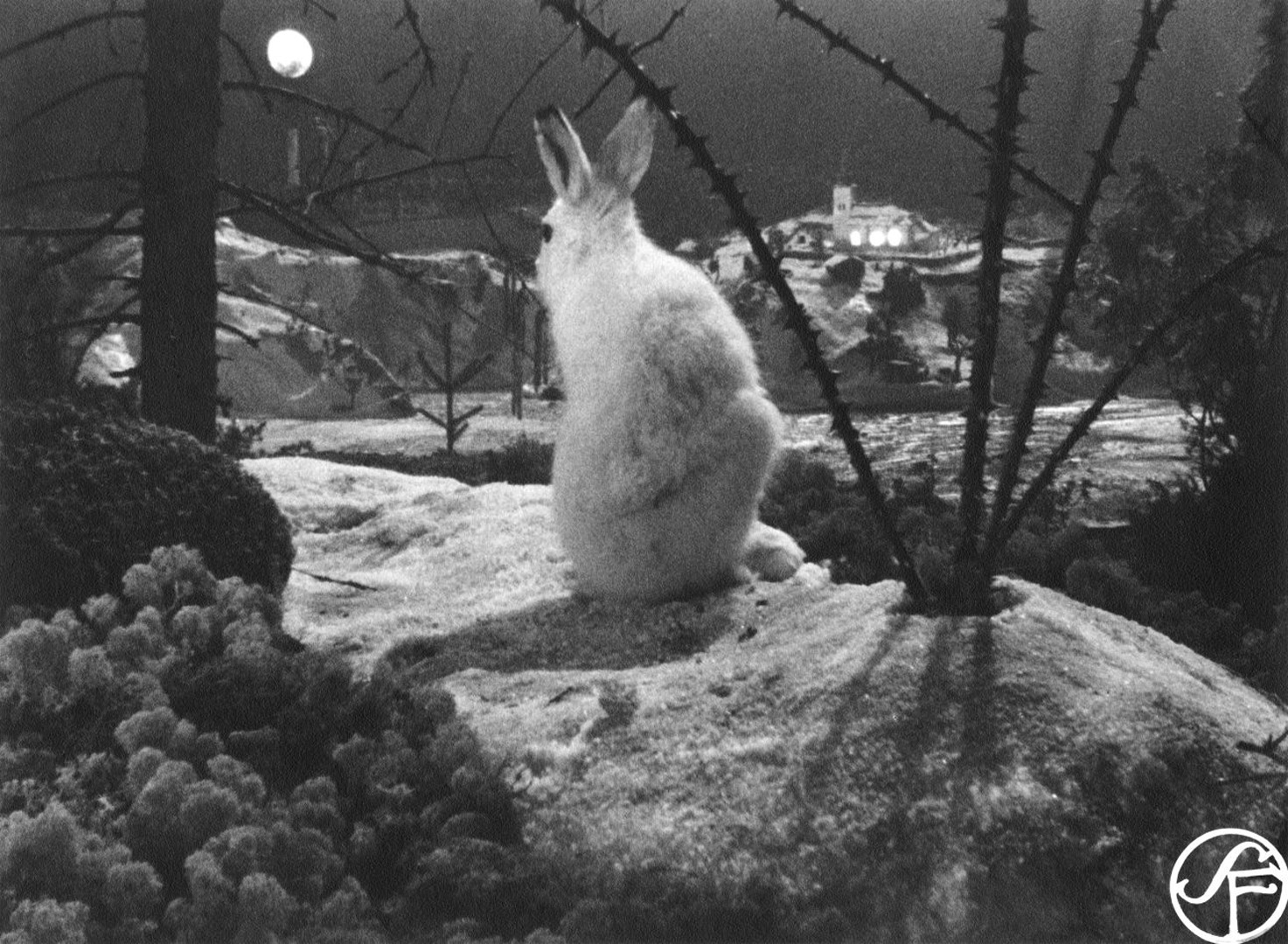

일본 애니메이션 감독 미야자키 하야오가 가장 좋아하는 작품 중 하나로 꼽는 월트 디즈니의 실리 심포니 시리즈 후기 작품인 〈오래된 물레방앗간〉은 인간 없는 세상에 사는 동물을 상상하며, 버려진 방앗간이라는 원시 인류세적 공간을 새롭게 창조하여 살아가는 이들의 모습을 보여 준다. 대조적으로 스웨덴 다큐멘터리의 선구자인 아르네 숙스도르프의 강렬하고 매혹적인 단편영화 〈분열된 세계〉 속 동물은 인간과 일정한 거리를 둔다. 이번에도 그는 건물을 이용하여, 성스러운 음악과 창문을 통해 빛이 새어 나오는 교회를 배경으로 인간과 동물의 거리를 나타낸다. 여기서 동물들은 여전히 독립적이지만 필멸의 존재, 어쩌면 도덕적인 존재로 여겨진다. 이 프로그램의 세 번째 작품이자 가장 최근작인 〈네 번〉에서 이탈리아 영화감독 미켈란젤로 프라마르티노는 인간과 동물을 함께 등장시켜 이들의 노동을 마치 하나의 느린 춤처럼 묘사한다. 인간과 동물의 노동이 오랜 시간 동안 주기적으로 반복되는 모습을 보여 주는 이 영화에서 인간과 동물의 세계는 드물게 대칭적이고 평등하게 그려지며, 음악적으로나 형이상학적으로 하나가 된다.

하버드 필름 아카이브에서 가져온 세 편의 아름다운 빈티지 35mm 필름을 통해 유기적이고 광학적인 영상 매체가 가진 뚜렷한 특성을 발견할 수 있을 것이다. 또한 이를 통해 소중한 생명력을 느끼게 하는 자연 세계에 관객이 훨씬 가까이 다가갈 수 있으리라 생각한다.

분열된 세계 A Divided World 감독 아르네 숙스도르프 Arne SUCKSDORFF | Sweden | 1948 | 8min | Documantary | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU

네 번 The Four Times 감독 미켈란젤로 프라마르티노 Michelangelo FRAMMARTINO | Italy, Germany, Switzerland | 2010 | 88min | Fiction | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU

If an animal could understand human language literally (rather than in terms of tone, temperature, pitch…) many expressions commonly used by filmmakers would certainly evoke fear or dread. Directors regularly speak, for example, of “shooting” a film and “capturing” footage of their subject, expressions that directly imitate the language of the hunt—of a human armed (in this case, with a camera) chasing after prey. Across its long and rich history, the relation of the cinema to animal has remained tethered to this idea of the hunt, to animals being chased, caught and “preserved” in a form of moving image taxidermy. Indeed, the history of cinema began, it could be argued, with a man and a camera aimed at an animal- the man was Eadweard Muybridge and the man was a horse. As a result, the default position throughout film history is to treat animals as subjects captured for specific scientific, aesthetic and narrative purposes.

This series of films offers three alternate, generative counter-positions taken by filmmakers towards animals, each from distinct historic periods and national cinemas. While this program’s films each reflect their respective culture’s distinct attitudes towards animals and nature in general, they cannot, however, simply be reduced to only a product of the time and time and place of their creation. Instead, the three films connect across film history to forge an inquisitive and progressive dialogue about animal agency and the limits of human and cinematic understanding. Ranging from popular animation, to religious allegory, to art house slow cinema, the three films nevertheless speak as well to different ways that animals continue to serve primarily as narrative devices- as (unpaid) actors of sorts asked to do the hard labor of carrying a film forward and engaging the audience.

A favorite of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, Walt Disney’s innovative late entry in its popular Silly Symphony series, The Old Mill (1937) imagines animals in a world without humans, reinventing through habitation the proto-anthropocene space of the abandoned eponymous mill. In contrast, pioneering Swedish documentarian Arne Sucksdorff’s stark and mesmerizing short A Divided World (1948) keeps humans at a measured distanced, again marked by a building but this time a church animated with holy music and the effulgent glow through its windows. Here the animals are still independent but seemingly judged as mortal and possibly moral creatures. In the third and most recent film in this program, The Four Times (2010) Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Frammartino man and animal are brought together into a slow dance that traces the longue durée of cyclical time of animal and human labor as synched to and working at the service of the same infinitely patient clock. In this film the human and animal world are given a rare symmetry and equity, as musically and metaphysically one.

This program brings together three beautiful vintage 35mm prints from the Harvard Film Archive in order to showcase the distinctly qualities of the organic, photochemical moving image and medium, so much closer to the natural world of the very animals to which they give precious life.