호주를 대표하는 독립영화 감독으로 사랑받는 빌 머술러스와 마고 내시는 서로 다른 세대에 속한다. 마고는 1970년대 반문화, 페미니즘, 공동체 운동에 몸담았고, 빌은 예술적인 슈퍼 8 영화 제작이라는 ‘포스트모던’ 영역에서 두각을 나타냈다. 이들의 미학적 스타일은 크게 다르지만, 시간이 흐르며 두 사람의 행보는 점차 비슷해졌다. 두 감독 모두 변화하는 시대 속에서 제작 방식과 자금 조달 방식 등에 새로운 가능성을 탐구해 왔으며, 개인적이며 때로는 도전적인 주제와 아이디어에 접근하는 다양한 방법을 모색하고 있다.

이들의 작품은 간결한 미니멀리즘부터 서정적 표현까지 대담하고 다양한 스타일을 선보이며, 사회적 틀에 도전하거나 그 안에서 개인적이고 친밀한 표현을 이어 간다. 또한 두 감독은 호주 영화문화에 깊이 관여하며 영화 연구, 저술, 교육, 상영회 기획 및 배급, 독립 영화인들을 위한 문화적·경제적 여건 개선 등 여러 분야에서 활발히 활동하고 있기도 하다. 한마디로 마고 내시와 빌 머술러스는 오늘날 호주 영화계의 생명력을 지켜 나가는 핵심 인물들이다.

인터뷰이: 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS, 마고 내시 Margot NASH 인터뷰어: 에이드리언 마틴 Adrian MARTIN

영화 제작에 뛰어들게 된 계기는 무엇인가?

마고 내시 1972년 배우로 불규칙한 일자리를 전전하던 시절, 멜버른 대학교에서 슈퍼8 영화 제작 강의를 하던 친구 로빈 로리와 함께 살고 있었다. 로빈은 멜버른대학교영화협회(MUFS)에서 활동했는데, 가끔 16mm 영화 프로젝터를 가져와 유럽 예술영화를 거실 벽에 비춰 감상하곤 했다. 그런 영화를 한 번도 본 적이 없던 나는 로빈과 영화에 대한 대화를 나누기 시작했고, 함께 영화를 만들어 보기로 했다. 이때 시나리오를 완성해 실험영화기금에서 1,300달러를 지원받았고, 이 프로젝트는 훗날 〈우리는 만족을 목표로 합니다 We Aim To Please〉(로빈 로리·마고 내시, 1976)라는 영화로 완성됐다. 당시 나는 촬영 보조 일을 시작했기 때문에 주말마다 장비를 집으로 가져와 직접 촬영했는데, 처음에 계획했던 시나리오는 중간에 폐기하고 새로운 아이디어를 영상에 담기 시작했다. 내 침실에서 오래된 수동식 ‘픽 싱크’ 편집기로 편집하는 과정에서 소리와 영상의 결합이라는 영화의 마법에 매료되고 말았다. 이 무렵 친구 집 거실 벽에서 본 장뤼크 고다르의 〈그녀에 대해 알고 있는 두세 가지 것들 Two Or Three Things I Know About Her〉(1967)과 멜버른 영화제작자 협동조합에서 관람한 마야 데렌의 〈오후의 올가미 Meshes of the Afternoon〉(1943)는 내게 매우 큰 영향을 끼쳤다.

빌 머술러스 십 대 시절 나에게는 음악과 만화책이 더 중요했고 영화는 큰 의미가 없었다. 열다섯 살 무렵에는 사촌과 함께 노래를 작곡하고 간단히 녹음하기 시작했는데, 내면의 창조적 욕구를 발산하는 방식이었던 것 같다. 열여덟 살이 되었을 때, 그리스계 이민자 가정의 자녀답게 의대나 법대를 가야 한다는 가족의 기대를 뿌리치고, 대학 진학 대신 1년 내내 집에 틀어박혀 텔레비전으로 방영되는 영화를 보기 시작하며 영화의 예술성에 빠져들었다. 1982년에는 상업 방송에도 꽤 수준 있는 작품들이 방영됐는데, (헤이스 규제 이전인 프리 코드 시대에 제작된) 프랭크 카프라 감독의 초기 작품들부터 존 포드, 하워드 호크스의 할리우드 고전, 장 르누아르, 잉마르 베리만 같은 유럽 작가주의 감독들의 작품까지 다양하게 접하면서 영화의 풍요로운 예술성에 심취했다. 그해 중반쯤 ‘나도 영화를 만들 수 있지 않을까?’라는 생각에 이르렀고 곧바로 긍정적인 결심을 했다. 이를 계기로 내 창조적 열망은 새로운 형태를 찾게 되었고, 그렇게 영화를 만들기 시작해 43년째 이어 가고 있다.

두 분은 독립영화인으로 볼 수 있을 것 같다. 예술적 창작과 제작의 현실적 측면에서 ‘독립영화인’이라는 호칭은 어떤 의미를 지니는가?

빌 머술러스 나 자신을 ‘독립영화인’으로 규정하고는 있지만 그것이 반드시 주류나 아트하우스 산업, 혹은 영화시장과 완전히 분리되거나 대립하는 위치를 의미한다고 생각하지는 않는다. 내게 있어 영화 제작의 출발점은 언제나 독창적인 아이디어였다. 내가 가치 있게 생각하고 소중하게 여기는 아이디어를 떠올리는 것이 우선이었고, 그다음이 그것을 실현할 방법을 찾는 일이었다. 처음 몇 년 동안은 완전히 독립적인 방식으로 작업했는데, 이번 전주국제영화제 상영 목록에 포함된 단편 〈끝없는 꿈〉도 이 시기의 작품이다. 영화학교를 다니지 않았고, 어떤 자금 지원도 받지 못한 상태라 말 그대로 ‘독립적인’ 상황이었다. 카메라 상점에서 슈퍼8 카메라를 판매하는 것을 보고 하나 구입했고, 1982년부터 84년까지 제작한 초기 작품들은 전적으로 혼자 힘으로 만들었다. 배우는 친구, 가족, 친척 들이었는데, 일례로 〈끝없는 꿈〉에는 내 여동생이 출연한다. 이후 일부 단편 및 장편 시나리오로 정부 지원금을 받게 되었지만 2000년 무렵부터 호주 영화계는 예술적 프로젝트의 가치를 점점 덜 인정하기 시작했고, 대안적 성격의 영화인들에게는 더 이상 자금이 지원되지 않게 되었다. 결국 최근 몇 년간은 개인 자금으로 영화를 만들고 있다. 만약 유럽이나 아시아, 또는 북미에서 활동했다면 좀 더 많은 산업적 지원을 받아 큰 규모의 예산으로 영화를 만들 수 있었을 텐데. 물론 그 경우에도 예술적 정체성과 창작의 자율성은 반드시 지켰을 것이다.

마고 내시 나에게 있어 ‘독립영화인’이라는 것은 본질적으로 체제 밖에서 작업한다는 의미다. 창작 측면에서는 상업적 압박으로부터 벗어나 예술적이든 정치적이든 과감한 아이디어를 실험할 수 있는 자유를 뜻한다. 미국에서 말하는 ‘체제’는 텔레비전을 포함한 다른 형태의 기업 시스템이나 할리우드 스튜디오 시스템을 지칭하지만, 호주에는 그러한 구조는 존재하지 않는다. 호주의 독립영화인들은 스튜디오 경영진에게 보고할 필요는 없지만, 대부분 정부의 자금 지원 기관에 의존해 왔다. 이러한 기관들은 점점 더 위험 회피적 성향을 보이며, 시장성과 수익 가능성에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 영화 제작은 저렴한 디지털 기술을 활용하더라도 여전히 비용이 많이 드는 작업이다. 이로 인해 제작 자금을 확보하는 경쟁이 치열해졌고, 자금을 지원하는 측은 누가, 어떤 프로젝트에, 어떻게 돈을 쓸 수 있는지에 대해 점점 더 많은 통제권을 행사하고 있다. 1970년대의 실험영화기금 시절은 이미 끝났고, 지금은 시장 논리가 지배한다. 오늘날 진정한 의미의 독립영화란, 개인 자금이나 크라우드 펀딩, 혹은 후원자들의 기부에 의존하는 저예산 영화뿐이다.

오늘날에도 여전히 영화 작업을 지속하며 관객과 만나고 있는 두 분 감독을 ‘생존자’라 표현하고 싶다. 물론 지금까지 제작되지 못한 프로젝트 등 수많은 좌절과 공백기를 겪었을 텐데, 많은 독립영화인들이 그 과정에서 포기하게 되고, 그런 결정은 충분히 이해할 만한 경우가 많다. 그렇다면 지금까지 영화계에 남아 있을 수 있었던 신념이나 조건은 무엇이었는가?

빌 머술러스 마고나 나와 같은 사람이 어떤 힘에 의해 움직이는지를 생각해 보면 영화 제작에 대한 강렬한 추진력, 거의 강박에 가까운 열망이 있는 것이 분명하다. 이는 실존적이고 철학적인 차원으로 이어지며, 심리적인 요소 또한 무시할 수 없다. 나는 다소 극단적으로 들릴 수 있는 니체의 말, “예술은 삶의 구원이다”라는 명제에 매우 깊이 공감한다. 많은 예술가들이 그러했듯, 나 역시 영화를 통해 얻는 충족감을 다른 방식으로는 도저히 느낄 수 없는 것 같다. 물론 열정이라 부를 수 있는 내 영화 인생 전반에 걸쳐 수많은 좌절과 실망을 경험했다. 예를 들면 삼십 대 중반 무렵 잠시 겪었던 우울증 같은. 그러나 영화가 주는 절대적인 기쁨과 성취감은 언제나 영화에 대한 열정을 잃지 않게 해준다.

마고 내시 나는 영화 제작을 진심으로 좋아한다. 몇 년 전 큰 프로젝트가 무산되었을 당시, 생계를 유지하고 거주지를 마련하기 위해 어쩔 수 없이 강단에 서야 했지만 그 와중에도 영화를 만드는 일은 멈추지 않았다. 종종 가족이나 친지의 성취를 축하하거나, 생일을 기념하거나, 고인을 추모하는 내용을 담아 선물하기 위한 소규모 영상 작업들을 이어 갔다. 이런 홈비디오 작업은 편집에 대한 갈증을 해소해 주었고, 제작 그 자체로 매우 즐거웠다. 또 이 시기에 제작으로는 이어지지는 않은 장편 시나리오를 여러 편 집필했는데, 이 작업은 내 영화적 기술을 발전시키는 데에도 도움이 되었다. 18년 동안 대학 강의를 하면서는 〈콜 미 맘 Call Me Mum〉(2005)과 〈더 사일런스 The Silences〉(2015), 이 두 편의 장편영화밖에 만들지 못했지만 둘 다 영화제와 극장에서 상영되었다. 첫 번째 작품은 6개월간의 휴직 기간을 활용해 만들 수 있었고, 두 번째 작품은 국제 예술가 레지던시의 지원으로 한 학기를 비우고 제작에 착수했는데, 시작하기까지 시간이 좀 걸렸고 최종 완성까지는 이후 3년이 더 소요되었다. 교수로 재직 중일 때는 대부분의 창작 에너지를 학생들을 돕는 데 쏟았지만 은퇴하자마자 다시금 직접 영화 작업에 몰두할 수 있었다. 2023년 전주국제영화제에서 상영된 단편 〈언더커런츠: 힘에 관한 명상〉은 자비로 제작한 작품으로, 내 이전 영화에서 추출한 이미지와 사운드를 재활용하거나 재구성해 완성했다. 애초부터 제작지원금을 신청하지 않았는데, 현재의 심사 기준으로는 선정되기 어려울 것임을 알고 있었기 때문이다. 그저 말하고 싶은 바가 있었고, 그것을 실현할 수 있었기에 직접 실행에 옮겼다.

두 분의 작업은 모두 1970년대의 유명한 구호, 즉 ‘개인적인 것이 곧 정치적인 것이다(The personal is political)’라는 명제를 각기 독자적으로 구현한 사례라고 생각한다. 그렇다면 두 분은 작업에서 개인적인 삶과 정치적 이슈가 어떻게 맞물린다고 보는가? 개인과 정치의 대화는 작품 속에서 어떻게 표현되나?

마고 내시 ‘개인적인 것이 곧 정치적인 것이다’라는 문구는 나에게 있어 페미니즘과 밀접히 연관되어 있다. 1970년대에 젊은 페미니스트였던 우리는 계급을 불문하고 여성의 경험이 과소평가되거나 아예 역사에서 삭제되어 왔다는 사실을 배웠다. 여성의 욕망과 부당함에 대한 저항은 억압되거나 하찮게 여겨졌으며, 미디어 속 여성의 이미지는 수동적이고 남성의 욕망을 충족시키기 위해 조형되었다. 많은 여성들이 차별과 고립이라는 개인적인 경험을 공유한다는 사실을 깨달았고, 이는 곧 우리가 결코 혼자가 아님을 뜻했다. 이에 대해 공개적으로 말하고, 영화로 표현하는 행위 자체가 곧 정치적 행위가 되었다. 나는 이와 같은 역사적 공백과 침묵, 억눌린 여성의 욕망에 대해 이야기하는 페미니즘 영화들을 자주 협업 형식으로 제작하기 시작했다. ‘개인적인 것이 곧 정치적인 것이다’라는 표현은 반대 의견을 진압하고 권력을 강화하기 위한 지배적인 사회 구조에 의해 억눌려 온 개인의 경험이 발현된 시민권 운동이나 다른 사회운동에서도 쓰였는데, 이 문장은 결과적으로 개인의 경험이 체제 비판과 직결된다는 사실을 명확히 보여 준다. 내가 만든 모든 영화가 나의 개인적인 경험에 관한 것은 아니지만, 내 작업 전체를 관통하는 핵심 개념은 바로 이 지점이다.

빌 머술러스 결국 모든 것은 정치적인 것이며, 혹은 철학적이거나 이데올로기적이라고 할 수 있다. 그저 표현 방식이 다를 뿐이다. 마고의 작업은 나보다 훨씬 더 문자 그대로 정치적이며, 그녀의 무정부주의적, 페미니즘적 활동 이력이 영화 작업 및 문화적 활동과 깊이 연결되어 있다. 우리 두 사람 모두 단순한 영화감독에 그치지 않고, 수년간 영화 협동조합, 영화 잡지, 큐레이션 등 다양한 형태로 영화문화 활동에 깊이 관여해 왔다. 작품 속 개인적이고 정치적인 요소의 표현으로 돌아가 보면, 나의 경우에도 개인과 정치 사이의 대화는 분명 존재한다. 특히 2009년부터 2017년까지 그리스에서 활동하던 시기의 작업은 보다 직접적으로 정치적인 내용을 다뤘지만, 그 외의 작품에서는 사랑과 살인이라는 양극단 사이에서 인간 존재를 조명함으로써 내용과 주제에 있어서 정치적 성격을 내포하고 있다고 생각한다. 나는 장르 대신 인간의 조건을 탐구하고자 하며, 그 안에는 인도주의적 태도가 깊이 스며들어 있다. 욕망과 절망에 관한 나의 이야기들은 어떤 의미에서는 페미니즘이나 퀴어 이슈를 다루는 영화들과도 다르지 않다. 결국 모든 것은 인간 존재의 경험, 인권 수호와 각 개인의 성향을 존중하는 문제로 귀결된다. 이와 같은 관점은 마고나 내가 수행해 온 영화문화 활동, 특히 호주에서 주류에 포함되지 못한, 소외된 혹은 대안적인 영화 제작자들을 중요하게 생각하고 지원하려는 노력을 통해서도 나타난다.

호주의 주류 영화는—물론 몇몇 훌륭한 예외도 존재하지만—대개 줄거리, 인물, 연기, 배경 등 ‘내용’에 더 큰 관심을 두는 반면, ‘형식’이나 영화적 언어에 대한 세심한 접근은 부족한 편이다. 특히 지적 담론, 영화 이론, 1970년대 이후 〈필름 뉴스 Filmnews〉나 〈센스 오브 시네마 Senses of Cinema〉와 같은 저널을 통해 발전해 온 비평문화에 대해서는 더욱 무관심하거나 이를 난해하고 실제 제작과는 무관한 영역으로 치부하는 경향이 있다. 두 분은 영화 형식에 대해 어떤 인식을 가지고 작업을 해왔는가? 그리고 진지한 영화비평이나 담론 문화가 두 분의 창작에 어떤 영향을 주었는가?

빌 머술러스 정확히 짚었다. 우선 1970년대 초반은 호주 영화계가 이제 막 태동하며 여러 경로를 실험하던 시기였다. 그 당시엔 엉뚱하고 실험적인 독립영화, 외설적인 코미디, 대중적인 아트하우스 영화들이 공존했지만, 〈행잉록에서의 소풍 Picnic at Hanging Rock〉(피터 위어, 1975)의 등장 이후, 호주는 점차 안전하고 잘 다듬어진 평범한 수준의 ‘품격 있는 영화’라는 길을 택하게 된다. 그 이후로 (지적으로 수준 높은) 독립/대안 영화와 주류 영화 사이의 간극은 점점 벌어졌고, 오늘날인 2025년에 이르러서는 호주의 주류 영화는 국제적으로도 별다른 가치가 없는 듯하다. 내 작업에서 나는 사실주의, 휴머니즘, 형식주의를 모두 동등하게 중요하다고 여긴다. 물론 모든 작품에서 이 세 가지가 항상 균형 있게 공존하는 것은 아니다. 내 영화 중에는 다분히 실험적인 것도 있고, 극영화, 다큐멘터리, 에세이 필름 등 다양한 형식과 방식이 존재한다. 주제도 중요하지만 결국 영화는 ‘형식’이라고 본다. 영화란 전적으로 형식에 관한 예술이다. 그리고 진지한 영화비평에 대해서는 나는 학자도 아니고 지식인도 아니지만, 비평에 늘 자극을 받아 왔다. 특히 당신(인터뷰어인 애드리언 마틴)이나 존 플라우스 같은 평론가들이 보여 주는 열정과 작품에 대한 통찰력은 항상 내 창작욕을 자극했다. 참고로 내가 1999년에 창간한 온라인 영화 저널 〈센스 오브 시네마〉는 지금도 운영되고 있는데, 그만큼 비평에 대한 애정을 가지고 있다.

마고 내시 로빈 로리와 내가 여성의 섹슈얼리티를 주제로 한 실험영화 〈우리는 만족을 목표로 합니다〉를 만들 당시, 우리는 여성의 표상에 관한 로라 멀비의 기념비적 이론 에세이 「시각적 쾌락과 내러티브 영화 Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema」(1975)를 읽기 전이었다. 아마 그 논문을 읽었더라면, 뭔가 잘못할까 두려워서 영화를 만들지 못했을지도 모른다. 당시 많은 페미니즘 이론을 읽고 접했는데, 흥미롭게도 시각적 재현과 남성의 시선에 대한 존 버거의 『다른 방식으로 보기』(1972)에서 매우 직접적인 영향을 받았다. 고다르에게서도 영향을 받았는데, 제4의 벽을 가볍게 허물며 영화 형식의 실험을 독려하고, 특히 관객을 향해 직접 말하는 방식에서 큰 영감을 얻었다. 내가 영화 작업에 점점 더 몰입하면서, 영화 이론과 비평 담론은 점차 중요한 역할을 하게 되었다. 영화가 어떻게 당대의 권력 체제를 지지하고 재생산하는지를 이해하고 싶었고, 그런 부분은 어렵지만 또 지적 호기심을 자극하는 부분이었다. 철학이나 정신분석학을 활용한 새로운 물결을 몰고 온 영화 이론가들은 그러한 권력 시스템을 돌파할 수 있는 새로운 영화 형식과 보기 방식은 무엇이 있을지를 끊임없이 고민하게 만들었다. 하지만 이론과 실제는 다르다. 창작의 과정은 때로 논리가 아닌 직관에 따라 ‘알 수 없는 영역으로 자유낙하’하는 것인데, 이 신비로운 공간에서 이론은 때때로 그런 흐름을 방해하기도 한다. 나는 전통적인 영화는 만들고 싶지 않았지만, 수년간 대학교에서 시나리오 작법을 가르쳐야 했기 때문에 구조와 캐릭터, 플롯, 미장센 같은 기본기를 반드시 다뤄야만 했다. 하지만 동시에 기존 규칙을 재해석하고 영화 형식을 실험적으로 바꾸어 온 흥미로운 감독들의 방식도 함께 탐구하며 가르쳤다.

두 분 모두 교육과 영화 배급/상영에서부터 비평적 글쓰기와 호주 독립영화 홍보에 이르기까지 넓은 의미에서 ‘영화문화’라고 부를 수 있는 영역에서 다양한 활동을 해왔다. 또한 페미니스트 그룹, 영화제작자협동조합, 슈퍼8 필름 운동 등 다양한 공동체 기반의 경험에 적극적으로 참여한 바 있다. 이러한 활동의 의미와 필요성은 무엇이라고 생각하는가?

마고 내시 한 단체나 집단의 일원이 된다는 것은 자신만의 ‘부족’, 즉 공동체를 찾는 데 도움을 준다고 생각한다. 다른 예술과 마찬가지로, 독립영화 제작자로서의 삶은 외롭기 쉽기 때문에 더 큰 공동체의 일원이 되어 소속감을 느낄 수 있다. 내가 초창기에 사귄 많은 친구들은 여전히 친구이자 동료로 남아 있고, 이러한 관계들은 아직까지도 매우 소중하다. 나는 1970년대에 우부(Ubu) 필름그룹에서 자신들의 영화를 상영하고 배급하고자 하는 욕구로부터 시작한 시드니영화제작자협동조합(Sydney Filmmakers Co-op)에 참여했는데, 그 당시까지는 실험영화, 원주민 영화, 페미니스트 혹은 정치 다큐멘터리 같은 작품을 보고 싶어 하는 관객이 없을 것이라는 통념이 지배적이었다. 그러나 협동조합은 이러한 생각이 틀렸음을 증명했다. 한때 그곳에서 16mm 필름을 청소하는 일을 했었는데, 이 필름들은 학교, 노동조합, 대학, 혹은 벌레가 붙은 채로 사막지대에서 되돌아 온 것들이었다. 당시 협동조합에 있던 원주민 흑인 직원은 프로젝터와 원주민 영화를 스테이션 왜건 뒷칸에 싣고 외딴 지역으로 가져가 상영했다. 시드니 도심에는 협동조합에 속한 작은 영화관이 있었고, 우리 영화를 리뷰, 토론, 홍보할 수 있는 〈필름 뉴스〉라는 신문도 있었다. 영화는 보여지고, 관객과 소통하기 위해 만들어지는 것이기 때문에 영화 홍보와 영화문화 활동에 참여하는 일은 독립영화 제작자에게 있어 매우 중요하다. 특히 제작자가 정보를 얻고 영화를 세상에 알릴 수 있는 기회를 제공한다. 나는 학자가 된 이후에야 비로소 영화를 연구하고 글을 쓰기 시작했는데, 이 작업이 놀라울 만큼 즐겁다는 것을 경험했다. 지금까지 창작 과정의 불확실성, 영화 기획개발, 각색, 서브텍스트, 다른 감독들의 작업, 그리고 호주 무성영화 시기의 여성 영화감독들에 관한 글을 출판했다.

빌 머술러스 나와 마고 둘 다 영화의 문화적인 측면에 자연스럽게 끌렸다는 사실은 꽤 놀랍다고 생각한다. 대부분의 감독들처럼 그냥 영화 제작에만 집중하는 “미친 예술가”가 될 수도 있었지만, 우리 둘은 서로 다른 도시에서 영화 문화계에 참여하는 길을 선택했다. 나의 경우, 영화에 대한 애착이 이런 결과를 낳았다. 진정으로 영화를 사랑한다는 것은 주류가 아닌 대안적 영역 안에서, 영화의 모든 측면을 사랑한다는 뜻이라고 생각한다. 물론 여전히 영화 자체가 가장 중요한 것, 즉 영화를 둘러싼 모든 활동의 ‘1차적 대상’임에는 틀림없지만 홍보나 토론 등 영화를 둘러싼 모든 활동 역시 중요하다. 최소한 그 활동들이 영화가 관객과 만날 수 있도록 해주고, 사람들이 영화를 보고 즐기고 이야기할 수 있게 하기 때문이다. 이러한 활동은 정치적이거나, 약자이거나, 초현실적인 사고를 하는 영화감독과 같은, 명백히 대안적인 영역과도 연결되어 있다. 주류 영화계, 특히 호주에서는 유행과 상업성에만 의존하는 경향이 강하다. 그리고 최근의 호주 영화 지원기관들은 (수십 년 전과 달리) 영화문화 활동에 거의 자금을 지원하지 않는다. 대안적이거나 역사와 관련한 프로젝트는 더욱 그러하기 때문에 대부분의 프로젝트는 직접 손으로, 저예산 수작업 방식으로 이루어진다. 그래서 나는 호주 독립영화를 위해 웹사이트를 만들고 상영회를 조직하는데, 모두 무상으로 하거나 혹은 독립영화 제작자 커뮤니티의 도움을 받아 해나가고 있다.

두 분 모두 70년대(마고 내시)와 80년대(빌 머술러스)부터 슈퍼 8, 16mm, 35mm, 디지털, 텔레비전용 영화 등 다양한 기술 형식과 규격을 넘나들며 작업해 왔고 다큐멘터리, 픽션, 실험영화, 개인 에세이 등 다양한 장르를 탐구해 왔다. 거의 모든 것이 디지털화된 시대에 접어든 21세기의 지금, 본인들의 작업이 어느 지점에 ‘도달’했거나 ‘정착’했다고 느끼는가? 아니면 표현을 향한 끊임없는 탐색이 여전히 계속되고 있는가?

빌 머술러스 표현을 향한 끊임없는 탐색은 확실히 계속된다고 생각한다. 기술은 늘 변화하는데, 그것은 당연한 일이다. 나는 필름 포맷을 선호하긴 하지만 2020년대의 디지털 시네마는 90년대, 2000년대 초기에 비해 상당히 괜찮은 수준에 이르렀다고 본다. 어쨌든 독립영화 제작자로서 우리는 감당할 수 있는, 혹은 접근 가능한 기술을 사용할 수밖에 없다. 영화를 만들고자 하는 욕망이 필름 규격 같은 표면적인 문제를 뛰어넘기 때문이다. 하지만 장르나 형식에 있어서는 정착하는 순간 곧 길을 잃는다고 생각한다. 내 영화 경력 초반 25년 동안, 특히 장편 혹은 내러티브 기반 영화에서는 하나의 주제 혹은 형식을 반복하며 변주하는 작업을 해왔다고 본다. 주로 유럽 미학에 영향을 받은, 절제된 예술영화 스타일이었고, 사랑, 살인, 욕망 같은 주제를 다루었다. 이후 그리스에 머물던 시기에는 정치적인 성격이 짙은 다큐멘터리 형식의 영화 〈거칠고 귀중한 Wild and Precious〉(2012)과 〈혁명의 노래 Songs of Revolution〉(2017)를 만들었다. 최근에는 〈스털링의 내 사랑〉이라는 뮤지컬 장르영화를 만들었고, 다음 영화 역시 장르적 접근을 시도할 계획이다. 지금까지 만든 11편의 장편 외에도 100편이 넘는 단편들을 제작했는데, 매우 다채롭고 실험적이며 유쾌한 작품들이다.

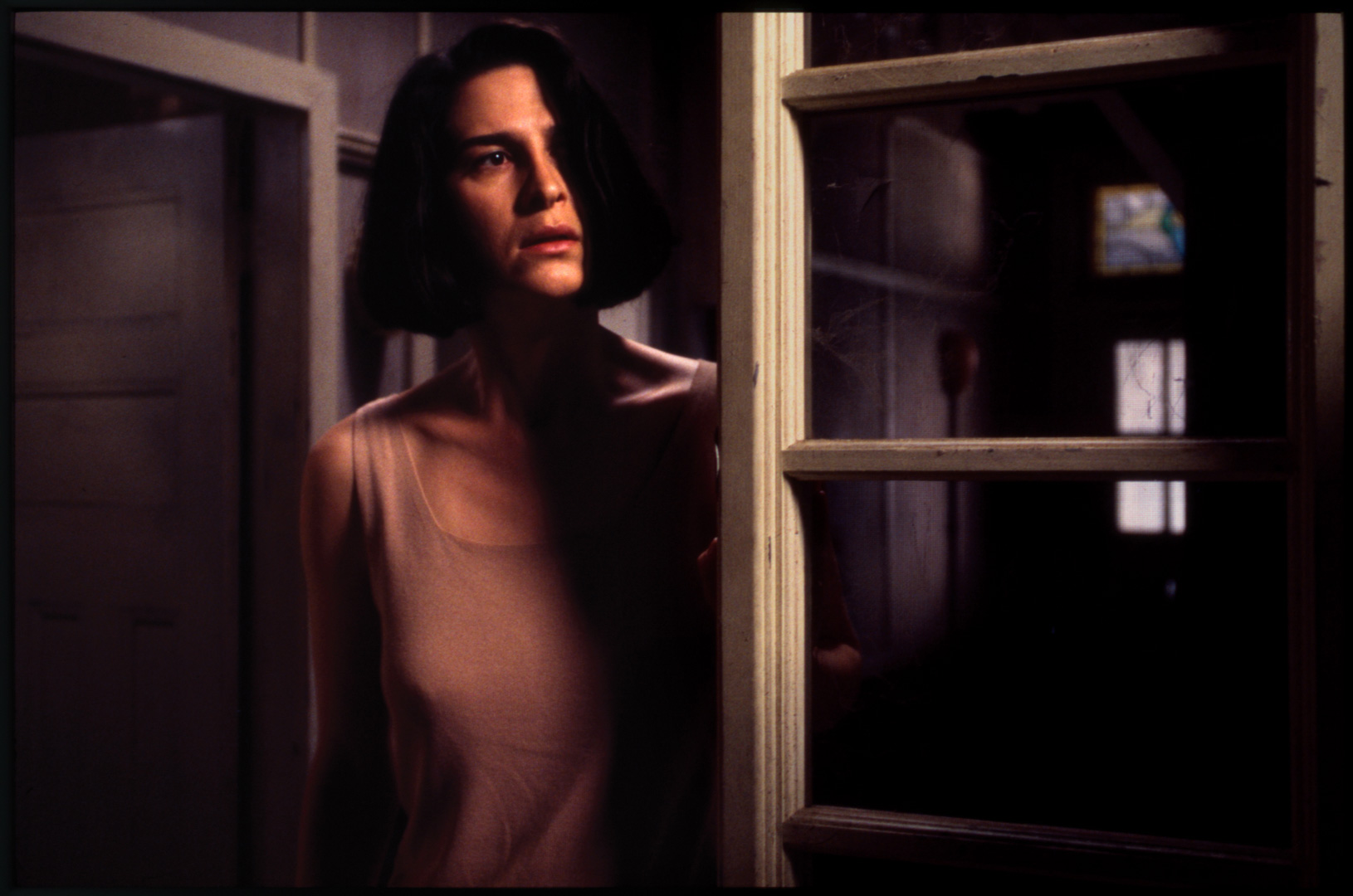

마고 내시 표현을 향한 끊임없는 탐색은 여전히 계속된다고 생각한다. 특히 기존의 보수적이고 시장 지향적인 기획개발 과정을 따르지 않는 영화를 만들기 위해 자금을 마련하는 일이 매우 어렵기 때문이다. 나는 많은 시각 예술가들처럼 발견 중심의 창작 과정을 선호한다. 시각 예술가는 아이디어를 탐색하는 창작 개발 과정을 위해 자금 지원을 받을 수 있지만, 영화 제작자는 아이디어를 구체화하는 개발 단계에 대한 제작 자금을 받기 위해서도 청사진처럼, 구체적으로 영화의 밑그림을 그려야 하고 실제 제작 자금을 받는 것은 더욱 어렵다. 그래서 가능한 한 기존의 지원기관을 피한다. 최근에는 편집실에서 내 아카이브를 활용하는 저예산 작업 방식을 실험해 보았다. 모든 것이 디지털화된 현재, 우리는 HD에 익숙해졌기 때문에 기존 아카이브 자료를 사용하려면 HD로 복원하거나 디지털화해야 한다. 대부분의 내 영화가 이미 디지털 복원되었고, 덕분에 복원 영화 프로그램에서 새 생명을 얻었으며, 편집실에서 새로운 작업을 할 때 사용할 수 있게 되었다. 슈퍼 8과 16mm로 제작된 내 모든 영화는 현재 디지털화됐다. 복원된 장편 드라마 〈무소유〉의 장면을 개인 에세이 다큐멘터리 〈더 사일런스〉에 사용했으며, 내가 만든 다른 영화들의 장면도 함께 인용했다. 이후 〈무소유〉의 다른 장면을 시적 에세이인 다큐멘터리 〈언더커런츠: 힘에 관한 명상〉에서 새롭게 재구성했고, 두 작품 모두 올해 전주국제영화제에서 상영된다. 이렇게 내가 저작권을 보유하고 있는 내 작업물을 직접 인용하는 방식을 통해 고화질의 이미지를 활용해 저예산 실험영화를 자유롭게 만들 수 있었다. 또한 2019년에 협업했던 마오리 예술가이자 안무가인 빅토리아 헌트의 아카이브와도 함께 작업해 단편 〈테이크 Take〉도 만들었다. 헌트의 창작 개발 워크숍과 공연이 영상 기록으로 남아 있었고, 아카이브 사진도 사용할 수 있었다.

이번 프로그램에 포함된 다른 영화, 커린 캔트릴의 〈이 생의 몸〉(1984)에 대해서는 어떻게 평가하는가? 이 영화를 처음 본 건 언제였는지? 지금은 이 작품을 ‘호주의 고전’으로 보아야 한다고 생각하는가?

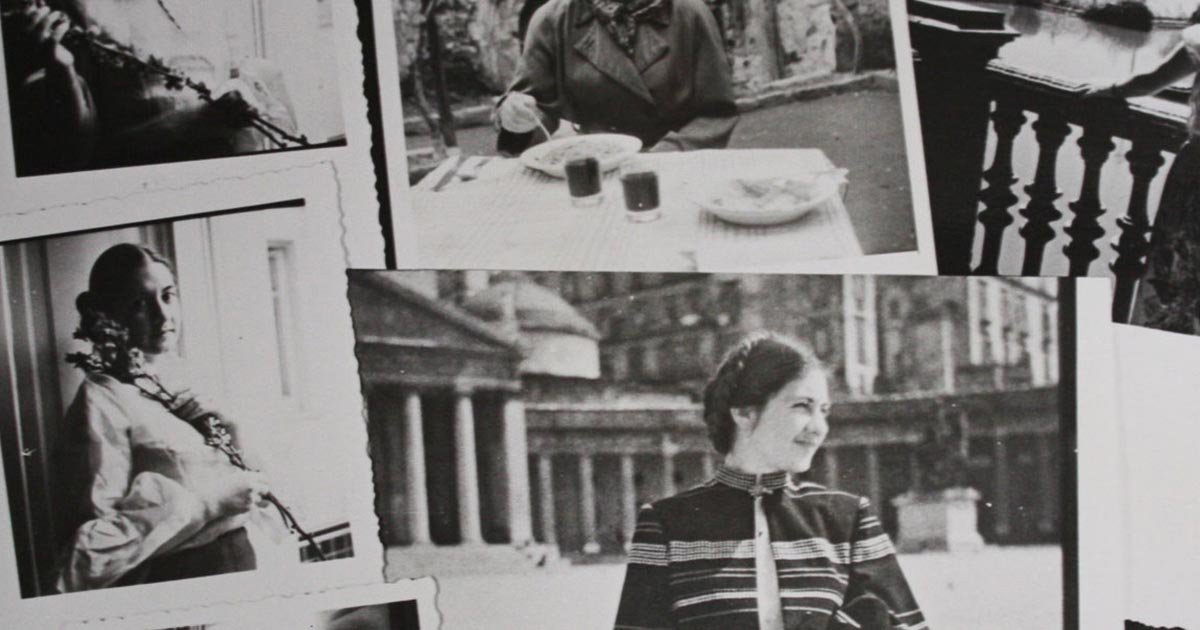

마고 내시 〈이 생의 몸〉은 확실히 고전이라고 생각한다. 수년 전 커린이 무대에서 태극권을 선보이며 배경으로 이 영화를 틀어 두었는데, 그렇게 영화를 처음 본 이후 줄곧 좋아해 왔다. 라이브 공연과 강둑에 나체로 누워 있는 커린의 모습을 담은 흑백 네거티브 이미지의 조합이 기억 속에 인상 깊게 남아 있다. 타협 없이, 날것 그대로의 이 영화는 커린의 개인적인 세계로 우리를 깊이 끌어들인다. 층층이 쌓인 상처, 갈망, 욕망을 벗겨 내며 알려진 것과 알려지지 않은 것 모두를 탐색한다. 사랑, 아름다움, 용기… 그리고 영화 자체를 발견해 나가는 여정이다. 이 영화는 내가 〈더 사일런스〉를 만들 당시 큰 영감을 주었다. 커린이 자신의 목소리와 스틸 사진들을 주로 활용해 이야기를 풀어가는 방식은 매우 철저하고 치밀하게 개인 아카이브를 파헤치는 작업이다. 그녀는 암 진단을 받고 이 영화를 만들었는데, 나 또한 〈더 사일런스〉를 만들며 가족의 아카이브를 거침없이 탐색하고, 과거에 대해 솔직하게 말할 수 있는 용기를 내야 했다. 나는 이 작품에 대한 비평 에세이를 〈센스 오브 시네마〉에 기고하기도 했고, 교단에 있을 당시 이 영화를 대안적인 호주 영화사 수업에 사용할 수 있도록 커린으로부터 디지털 스캔에 동의를 얻기도 했다. 커린과 그녀의 남편, 아서 캔트릴은 호주 실험영화의 역사에서 독보적인 역할을 해왔는데 이 작품은 그들이 만든 보다 형식적인 아방가르드 작품들과는 다른 결을 가지고 있다. 영화 순수주의자였던 그들은 자신들의 실험영화를 반드시 원래의 16mm 필름 형식으로 상영하길 원했다. 그래서 전주에서 이 영화를 16mm 프린트로 볼 수 있다는 건 매우 큰 행운이다. 커린도 분명 기뻐했을 것이다. 그녀는 길고 창의적인 삶을 살다 최근 96세의 나이로 세상을 떠났다.

빌 머술러스 〈이 생의 몸〉은 정말 대단한 영화다. 다른 독립 장편이나 다큐멘터리, 단편 혹은 실험영화와 함께 호주 영화의 고전이라고 생각한다. 자신을 들여다보는 이 영화의 태도는 철저하고 예리하며, 형식적으로도 놀라울 만큼 엄격하다. 나는 이 영화를 1980년대 중반쯤, 처음 공개되었을 무렵이나 그 직후에 처음 접했다. 이후 다시 볼 기회가 없어서 아쉬웠는데, 올해 전주에서 이 작품을 볼 수 있다니 보러 가고 싶다. 최근 커린의 타계로 인해 호주를 비롯한 여러 곳에서 이 영화에 대한 관심이 다시 높아지고 있는데, 그것이 그녀의 남편 아서 캔트릴과의 공동 작업들이 이룬 성취들을 가리는 일이 되지 않기를 바란다. 그들의 작업과 유산의 폭과 깊이를 생각하면, 그런 일은 없을 것이라 믿는다.

스털링의 내 사랑 My Darling in Stirling 감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 2023 | 80min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

끝없는 꿈 Dreams Never End 감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 1983 | 10min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

실험 천사 The Experimenting Angel 감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 2010 | 8min | Experimental | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

야생 속으로 Into the Wild 감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Greece, Italy, Australia | 2011 | 7min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

무소유 Vacant Possession 감독 마고 내시 Margot NASH | Australia | 1994 | 95min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

언더커런츠: 힘에 관한 명상 Undercurrents: Meditations on Power 감독 마고 내시 Margot NASH | Australia | 2023 | 20min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

이 생의 몸 In This Life’s Body 감독 커린 캔트릴 Corinne CANTRILL | Australia | 1984 | 147min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin © Arthur & Corinne Cantrill

Bill Mousoulis and Margot Nash are among the most prominent and beloved independent filmmakers in Australia. They belong to different generations: Margot was part of the countercultural, feminist and collective movements of the 1970s, while Bill emerged in the ‘postmodern’ scene of artistic Super-8 filmmaking. Their aesthetics are quite distinct but, over time, their career paths have more closely come to resemble each other. Both of them are explorers of possibilities: possible ways of financing and making films across the contexts of changing times, and possible ways of approaching personal, often challenging themes and ideas. Their films are characterised by bold uses of cinematic style – from the tersely minimal to the highly lyrical – and by a commitment to personal, intimate expression within and against the prevailing social framework. They are both closely involved with the broader film culture of Australia: research, writing, teaching, the curating and presenting of films to the public, distribution, militating for better cultural conditions and economic opportunities for independent filmmakers. In short, Margot Nash and Bill Mousoulis are an essential part of the lifeblood of a still-vital Australian cinema today.

What was the trigger in your life that impelled you into filmmaking?

MARGOT NASH In 1972 I was an in-and-out-of-work actor, sharing a house with my friend, Robin Laurie, who was teaching Super-8 filmmaking at Melbourne University. She had been active in the Melbourne University Film Society (MUFS), and would sometimes bring home a 16mm film projector and project European art films on the lounge room wall. I had never seen films like that before. We started ‘talking film’ and decided to make a film together. We wrote a script and successfully applied for $1,300 from the Experimental Film Fund. This film would eventually become We Aim To Please (Robin Laurie & Margot Nash, 1976). I had started working as a camera assistant and would bring camera equipment home on weekends to film. We had abandoned the script and instead began to film new ideas. I edited it in my bedroom on an old hand-wound, ‘pic sync’ and, in the process, fell in love with film and the magic of putting sound and image together. Jean-Luc Godard’s Two Or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) which I saw on someone else’s loungeroom wall, and Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) which I saw at the Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op, had a major impact on me during this time.

BILL MOUSOULIS When I was a teenager, films meant very little to me – more important were music and comic books. As a 15-year-old I started writing songs and recording them in a very lo-fi way, with my cousin. This was an outlet for what was obviously a creative urge in me. Shoot forward to the age of 18 and I became a rebel to my family, refusing to go to university to study for a professional career in medicine or law (the expected thing for a child of Greek migrant parents). Instead, I stayed home all year and started watching films on the TV, and very quickly I was struck by their artistry. From early Frank Capra films (pre Hays code), to classic Hollywood films (Ford, Hawks), to European auteurs (Renoir, Bergman – yes, commercial TV in 1982 still had some quality on it), I was immediately smitten by cinema and its riches. Halfway through that year, I thought to myself – “I wonder if I also can make a film?” I answered categorically in the positive, and so my creative urge now had a new form, and one that has lasted so far to this day, 43 years later.

I regard you both as independent filmmakers. What does that label mean to you, in relation to your artistic creativity, and to the practicalities of production?

BILL Yes, I label myself an ‘independent filmmaker’, but I don’t necessarily see that as a position completely away from or antagonistic to the mainstream/arthouse industry or film marketplace. For myself, the main thing when I started was to come up with original ideas, ones I valued and cherished even, and then secondly to find the means to realise them. In my first few years (of which the short film Dreams Never End, in the Jeonju program, was a product), I truly was completely independent, as I didn’t go to any film school and had no access to any money from any source to make my films. I saw that Super-8 cameras were being sold in camera stores, so I bought one, and my first few films, from 1982 to 1984, were made solely by myself, using friends and family and relatives as actors (my sister, for example, in Dreams Never End). After that, I received government funding for some short films and feature-length scripts. Eventually however, starting from around 2000, the Australian film ecosystem stopped valuing more artistic projects, and the funds stopped flowing to the more alternative filmmakers. So, in recent years, I now simply make films with my own money. If I had lived my life in Europe or Asia or even North America, I would have been more supported by the ‘industry’ and made films with more money (but with the condition of course of always retaining artistic and my own individual integrity).

MARGOT For me, being an independent filmmaker essentially means working outside the system. Creatively, it means feeling free to push boundaries, and experiment with radical ideas, both artistically and politically, without the pressure to make something commercial. In America, ‘the system’ means the Hollywood studio system, which we do not have in Australia, but also other corporate systems such as television. While independent filmmakers in Australia are ‘independent’ in so far as they do not have to answer to studio executives, most of us have been dependent on finance from government funding bodies, with their increasingly risk-averse agendas and focus on market viability. Filmmaking is expensive, even using cheap digital technology, and raising finance for films has become extremely competitive, leading to more and more control being exercised by the funding bodies over who, and what, gets funded, and how the money is spent. The 1970s days of the Experimental Film Fund are well and truly over and ‘the market’ rules. These days, the only truly independent films are low-budget, self-funded films that rely on personal savings, crowd funding or philanthropic sources.

I also see the two of you as ‘survivors’, still making work today and getting it out there for audiences to see and experience. Yet you have undoubtedly experienced frustrations (unmade projects, etc.) and lulls in your career. Many independent filmmakers give up along the way, and often for quite understandable, valid reasons. What are the convictions and conditions that have kept you going ‘in the game’ all this time?

BILL What drives people like Margot and myself? Indeed, there is a great drive, almost a compulsion, to make films and to continue to make them. It goes to existential and philosophical questions, of course (and psychological ones, too). I agree with Nietzsche’s dictum that “Art is the salvation of life”, no matter how dramatic that may sound. As many artists have said about themselves, I wouldn’t know what else to do with my life that would still give me the deep fulfilment that cinema gives me. Yes, I have experienced setbacks and frustrations in my film career (or passion, let’s call it), including a short period of depression I had when I was in my mid-30s, but the absolute joy and fulfilment that cinema gives me always keeps me loving it.

MARGOT I love making films. Even when a major project fell over some years ago, and I had to put my head down and teach in order to survive and have somewhere to live, I still made films. Small projects that I edited and gave to my family, or extended family, celebrating the achievements of others, birthdays or the lives of loved ones who had died. These home movies kept my itchy editing fingers happy and gave me pleasure to produce. During this time, I wrote a number of feature length screenplays that were not produced, but each unproduced screenplay increased my skills and taught me something new. In the 18 years of teaching at the university, I only managed to make two major films, Call Me Mum (2005) and The Silences (2015), that had a public life on the film festival circuit and in the cinema. I took six months’ leave to make the first one and the second was developed through an international artist residency, where I took a semester off from teaching. Long enough to get the project going, but it took another three years to complete the film. Teaching meant most of my creative energy went into nurturing the creativity of others but, as soon as I retired, I started making films again. My short film Undercurrents: Meditations on Power (2023), screening at Jeonju, was self-funded and made by reimaging or recycling images and sounds from my previous film work. I didn’t even try to get funding, as I knew it would not ‘tick the boxes’. I just did it because I had something to say, and I could.

I interpret both of your careers as distinct, individual manifestations of that great 1970s slogan, ‘the personal is political’. How do you conceive of the interplay between personal life and political issues in your work? How does that dialogue of personal and political express itself?

MARGOT I associate ‘the personal is political’ with feminism. As young feminists in the 1970s, we learned that the experiences of women were undervalued and often written out of history, regardless of class. Women’s desires and women’s struggles against injustice had been repressed or trivialised, and images of women in the media were passive and sexually pliant in order to serve the interests of male desire. We learned that our personal experiences of discrimination and isolation were shared by other women. We were not alone, and to speak publicly about this, and make films about it, was political. I began to make feminist films, often collaboratively, which spoke about the gaps or silences in history, and about repressed female desire. ‘The personal is political’ was also used in the civil rights movement, and other social movements, where the experiences of individuals had been undermined and repressed by the dominant social system in order to crush dissent and consolidate power. ‘The personal is political’ directly connects personal experience with a critique of wider social structures of power. Not all my films are about my personal experiences, but all my films explore this concept.

BILL Yes, everything is political ultimately, or maybe we could say it’s philosophical or ideological, the term doesn’t matter that much. Margot’s career, more than mine, is more political in the literal sense of the word, with her rich history of anarchist and feminist activity, connecting to her film work and cultural work. Indeed, apart from being filmmakers ourselves, Margot and I have been very enmeshed in film cultural work over the years (film co-operatives, magazines, curating screenings, etc.). But, getting back to the personal and the political as expressed in our actual film work, yes, there is a dialogue there. For myself, the content and themes of my work (apart from the overtly political phase I had when making films in Greece between 2009 and 2017) are political in the way I highlight the human condition (between the poles of love and murder), as opposed to doing genre work for example. There is a humanitarianism involved and invested in these tales of desire and dejection that I have made. In a way, these themes are no different from feminist or queer themes for example – everything ultimately goes back to the matter and experience of being human, the upholding of human rights and the individual predilections of each human. And this also connects to the film cultural work Margot and I do and have done, as we always seek to value and promote the marginalised or alternative filmmakers in the Australian scene.

Much mainstream Australian cinema (with some excellent exceptions, of course) cares more about ‘content’ (plot, characters, acting, setting) than about fine-grain matters of ‘form’ or filmic language. And the mainstream cares even less about intellectual ideas, film theory, and the newer styles of film criticism that have flourished since the 1970s in places like the Australian publications Filmnews and Senses of Cinema – all of which it regards as largely esoteric and irrelevant to the business of making films. What’s your own awareness of film form, how do you work with that? And how does the culture of serious film discussion affect or influence you?

BILL You said it, brother. Firstly, there was a period in the early 1970s where the burgeoning Australian filmmaking scene was just finding its feet, it was hovering between the crazy independent films being made at the time, the bawdy comedies, and the middle-brow arthouse films coming into vogue. These forks were dissolved quickly though, as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) lead Australia down the safe, well-trodden path of the middle-brow, ‘cinema of quality’ film. Since then, the divide between the independent/alternative (and intellectually rigorous) film world and the mainstream film world has been widening and widening, to the point where now, in 2025, Australian mainstream cinema has little value (or estimation worldwide). In my own film work, I’ve always considered myself realist and humanist, but also formalist – all three being equally as important. Which is not to say that these three modes have been necessarily in balance in my films, as some of my films are more experimental than others, some are fiction, some documentary, some essay, there is a huge eclecticism to my work. And whilst the themes are important, really, cinema is form, fully it is form. As for serious film discussion, even though I myself am not an academic or intellectual person, I have always been inspired by film criticism, especially certain critics (like yourself Adrian, or John Flaus for example) who have individual passion and always say interesting things about the films they are discussing. The criticism then inspires my own film work. I guess it should also be noted that I myself founded the online journal Senses of Cinema in 1999 (still running today), so obviously I value criticism quite a lot.

MARGOT When Robin Laurie and I made our wicked little experimental film about female sexuality, We Aim To Please, we had not read Laura Mulvey’s seminal theoretical work about the representation of women, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975). If we had, I suspect we would have been too scared to make it for fear of doing the wrong thing! We were reading a lot of feminist theory, yet interestingly, it was John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) that directly influenced us in terms of the visual representation of women and the male gaze. Also Godard, who cheerfully broke the fourth wall and gave us permission to experiment with film form, in particular the direct address. As I became more engaged with filmmaking, the culture of film theory played a bigger role. I found it challenging and intellectually stimulating to explore different ways to understand, the way film worked culturally to support the current systems of power. Drawing on philosophy, and psychoanalysis, the new wave of film theorists challenged us to try and find different forms that might break through those systems of power, and create new ways of seeing. However, theory and practice are different and the creative process means ‘freefalling into the unknown’, with intuition rather than logic as guide. It’s a mysterious space, and one where theory can get in the way. I have never wanted to make conventional films, but I spent many years teaching screenwriting, so I had to teach the basics of structure, character, plot and mise en scène. But I also investigated, and taught, the way some of the more interesting filmmakers reimagined the conventions and experimented with film form.

You have both been involved in a range of activities that we can put under the broad umbrella of ‘film culture’, from teaching and film distribution/exhibition to critical writing and promotion of Australian independent cinema. You’ve both been part of ‘collective experiences’ such as feminist groups, the filmmakers’ co-operatives, or the Super-8 movement. What’s the importance and necessity of that kind of activity for you?

MARGOT I think being part of collectives and other groups helps you find your ‘tribe’, your community. Like any artist, being an independent filmmaker can be lonely, and being part of a wider group can create a sense of belonging. Many friends I made back in the early days are still my friends and colleagues, and I value those connections. I was involved with the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op, which was started in the 1970s by the Ubu film group, who wanted to get their films seen and distributed. Up until then, conventional wisdom had been that there wasn’t an audience for experimental films like this, or for Indigenous, feminist or political documentaries. The Co-op proved this wrong. I used to work there cleaning 16mm films that might have come back from schools, trade unions and universities or from the central desert with insects still stuck to them. We had an Aboriginal ‘Black Film Worker’ who put Indigenous films in the back of a station wagon with a projector and took them out to remote communities. We had a small cinema in inner-city Sydney and a newspaper called Filmnews, where our films could be reviewed, discussed and advertised. Films are made to be seen and engaged with, and being part of activities like the promotion of film and film culture is critical for independent filmmakers if they want to stay informed, as well as get their films out. It was only after I became an academic that I began researching and writing about film. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed this. I have published about creativity and the uncertain nature of film development, adaptation, subtext, the work of other filmmakers, and women filmmakers in the silent era in Australia.

BILL Yes, it’s quite remarkable that both Margot and I have been attracted to this film-cultural side of things. We could have easily just concentrated on our film work (like most filmmakers), and become ‘mad artists’, but we have both chosen, in different cities, to be involved in the film-cultural scene. For me, it’s the love of cinema that has created this. Loving cinema fully means loving every aspect of it (within the alternative sphere, not the mainstream one). Whilst I still believe films themselves are the most important things, the ‘primary objects’ of all the activity around them, all that activity (promotion, discussion) around them is still crucial, if for no other reason than to just make those films available, for people to watch and enjoy and talk about them. And this is clearly tied to the realm of the alternative – the political filmmaker, the underdog filmmaker, the surreal filmmaker. The mainstream world, especially in Australia, is limited to what’s in vogue and what’s commercial. And the film funding organisations in Australia these days (as opposed to a few decades back) have little money for film cultural activities, especially those revolving around the alternative or the historical, so a lot of this activity is also DIY, low-budget, hand-made. So, for Australian independent cinema, I create websites and organise screenings, all for no money whatsoever, or with help from the community of ‘indie’ filmmakers themselves.

Since the 1970s for Margot and since the 1980s for Bill, you have both traversed – like many independent filmmakers – many different technical formats and gauges: Super-8, 16mm, 35mm, digital, a film for TV – and also diverse genres of documentary, fiction, experimental, personal essay, and so on. Do you feel, now in this almost all-digital point of the 21st century, that you’ve ‘arrived’ or ‘settled’ anywhere in your practice, or does the restless search for expression continue?

BILL The restless search for expression continues, for sure. The technology is always changing, but that’s okay, that’s natural. I prefer the film gauges, but these days, in the 2020s, digital cinema looks pretty good, compared to its early days of the ‘90s and ‘00s. In any case, as independent filmmakers, we use the technology we can afford or have access to, because the desire to make films outstrips these more superficial questions of gauge. In terms of genres or forms, however, if one settles, one is lost. In a way, for my first 25 years of making films, yes, there was, within my feature or narrative film work, a practice where I was doing ‘variations on a theme’ (or a form/style) – mainly European-influenced, austere art cinema work around themes of love, murder, desire. After that, in my time in Greece, I made the two features Wild and Precious (2012) and Songs of Revolution (2017) that are mainly documentaries, and political ones at that. And more recently, my feature My Darling in Stirling (2023) is a genre film, a musical, and I am planning another genre-type feature next. It must also be noted that apart from these 11 features I have made, there have been over 100 shorts, too, over the years, and they are very eclectic, playful, experimental.

MARGOT I think the restless search for expression continues, particularly as it is so difficult to raise money to make films that do not follow the risk-averse, market-driven development process advocated by the funding bodies. I prefer a discovery-driven process, which is the way many visual artists work. Artists can raise money for a creative development process to explore ideas, but filmmakers have to plot out a film, like a blueprint, before getting money to even develop an idea, much less produce a film. This is why I try to stay away from the funding bodies, and have recently explored a low budget way of working with my own archive in the editing room. Everything is digital now, and we are so used to HD that archival materials need restoring or digitising to HD to use them. Most of my films have now been digitally restored, which has given them a new life in film festival restoration programs, but it has also meant they are available to me to work with in the editing room to produce new work. I have digitised all my Super 8 as well as my 16mm films. I used clips from my restored feature drama Vacant Possession (1994) in my personal essay documentary The Silences, as well as clips from other films I had made. Later I reimagined other clips from Vacant Possession in my poetic essay documentary Undercurrents: Meditations on Power – both are screening in Jeonju. This ‘quoting’ from my own body of work, where I own the copyright, has given me the freedom to make low budget experimental work, with high quality images. I have also worked with the archive of Maori artist/choregrapher Victoria Hunt, whom I collaborated with in 2019 to make a short called TAKE. She had videoed creative development workshops, as well as performances, and we had access to archival photographs.

What’s your estimation of the other film in the program, Corinne Cantrill’s In This Life’s Body (1984)? When did you first encounter it? Do you now regard it as an Australian classic?

MARGOT I think In This Life’s Body is definitely a classic. I have loved it ever since I first saw it many years ago, with Corinne doing Tai Chi on the stage in front of the image. The combination of live performance with a black and white negative image of Corinne lying naked on a river bank is imprinted in my memory. And the film – so uncompromising and raw – allows us into her personal world as she peels away layers of wounding, longing and desire, searching the known and the unknown. Discovering love, beauty, courage … and film. It was an inspiration to me when I was making The Silences. Her use of mainly still photographs, and her voice, to tell the story is such a rigorous and forensic dive into her personal archive, made when she was facing a cancer diagnosis. When I made The Silences, I too had to explore my personal family archive unflinchingly, and find the courage to speak honestly about the past the way Corinne had. I wrote a critical essay about In This Life’s Body in the journal Senses of Cinema and, when I was teaching, I managed to get Corinne to agree to a digital scan of the film, so I could use it in my alternative Australian film history class. Corinne and her husband Arthur have played a unique role in the history of Australian experimental film, but this film is different to the more formal avant-garde film works they have made. They were film purists and wanted their experimental work to be seen in its original 16mm form, so you are very lucky in Jeonju to be able to see a 16mm print. Corinne would have been pleased. She enjoyed a long and creative life, dying recently aged 96.

BILL In This Life’s Body is an incredible film, no doubt. I’d say it is indeed an Australian classic, along with a number of other alternative features or documentaries (or even shorts or experimental films). As a self-examination, it is thorough and cutting, and its form is magnificently rigorous. I first saw Corinne’s film around the time it was released (mid-1980s), or maybe a few years after that. I have not seen it again, alas, so I wish I was there at Jeonju to watch it again. I hope that the recent focus on the film (in Australia, and elsewhere) due to her recent passing away does not ultimately overshadow the achievements of her work with her husband, Arthur Cantrill. But I don’t think it will, considering the breadth and quantity of their work and legacy.