English text below

전주국제영화제의 26년을 관통하는 정신은 ‘대안’이다. 필름의 대안으로 ‘디지털’을 앞세워 출범한 전주국제영화제는 주류 영화의 대안으로 ‘독립영화’를 중심에 세웠고, 관습의 대안으로 ‘영화, 표현의 해방구’를 외쳤다. 그렇다면 경제 위기가 문화를 옥죄고, 정치적 상황에 따라 문화정책이 휘둘리고, 예술보다 산업에 방점을 두는 오늘날 우리 영화계에 필요한 대안은 무엇일까? 26회 전주국제영화제 특별전 ‘가능한 영화를 향하여’는 여기에서 시작되었다.

특별전 ‘가능한 영화를 향하여’는 아홉 팀의 창작자가 만든 열두 편의 영화를 소개한다. 올해 영화제 개막작이기도 한 〈콘티넨탈 ’25 Kontinental ’25〉를 연출한 라두 주데의 또 다른 영화부터 전주가 오래 주목해 온 마리아노 지나스 감독이 몸담고 있는 제작사 엘팜페로시네, 팀을 이뤄 자력으로 영화를 찍고 있는 한국의 제작사 사랑하자 등이 그 주인공. 어떤 상황에서든 ‘영화’를 최우선으로 두는 이들 창작자들에게 영화란 어떤 존재인지, 예술로서의 영화와 산업으로서의 영화 사이에서 어떻게 균형을 맞추고 있는지, 이 시대에 영화인으로 사는 것은 어떤 것인지를 묻기 위해 인터뷰를 진행, 단행본 『가능한 영화를 향하여 POSSIBLE CINEMAS』를 발간하였다. 여기에서는 특별전을 기획한 문성경 프로그래머가 진단하는 한국 영화계의 현실, 그리고 이들 창작자들에게서 우리는 어떤 영감을 얻어야 하는지를 전한다.

가능한 영화를 꿈꾸며

현재 산업 구조에서는 더욱 어려운 일이지만 ‘친밀감’이라는 개념에서 시작하는 영화를 만들고 싶었다. 서류로 나타내기 어렵고 대규모 자금을 설득할 수 없는 이야기, 재료, 배경에 관심이 있다. 다행히 나는 프로젝트를 진행하는 시간 동안 해야만 해서 일하는 사람들이 아닌, 자신의 본 모습을 간직한 사람들과 효율적으로 일하는 것을 좋아한다. 마티아스 피녜이로

“지금 전주국제영화제의 정신은 무엇인가, 무엇이어야 하는가?”

이는 영화제에서 상영할 한 편의 영화를 결정하는 순간에도 영화제의 방향성을 고민해야 하는 순간에도 따라다니는 질문이다. 지난해 전주국제영화제는 여러 감독에게 영화가 곧 사라질 예술 이라고 생각하는지를 묻는 다큐멘터리 〈룸 666 Room 666〉(빔 벤더스, 1982)을 상영했다. 여기에서 장뤼크 고다르는 “영화의 역사는 작은 영화에서 시작되었다”라고 말한다. 그리고 이 말은 26회 전주국제영화제 특별전 ‘가능한 영화를 향하여(Special Focus: Possible Cinemas)’를 구상하는 데에 영감을 주었다.

오늘날 ‘작은 영화’는 무엇을 뜻할까? 예산, 촬영 양식, 제작 방식 혹은 주류 영화산업에서의 독립 등 여러 부문에서 답할 수 있을 것이다. 고다르는 영화 경력의 마지막 작품들을 스위스 롤에 위치한 자신의 집에서 소수의 협력자들과 수작업으로 만들었다. 어쩌면 이 예가 질문에 대한 답이 될 수도 있겠다.

한국 영화계에서 전주국제영화제가 차지하고 있는 자리는 가장 독립적인 영화를 소개하는 것이다. 전주국제영화제는 2014년부터 ‘전주시네마프로젝트’라는 이름으로 국내외 장편영화 한 편에 최대 1억 원을 투자해 오고 있다. 투자금을 받은 감독은 다음 해까지 영화를 완성해 영화제 기간에 상영해야 한다. 장편 한 편 이상을 만든 창작자의 차기작을 지원하고, 저예산 영화 제작을 활성화하는 데 기여하겠다는 목표를 둔 전주시네마프로젝트는 올해까지 모두 서른일곱 편의 영화를 세상에 내놓았다. 하지만 최근 들어 1억 원을 받고도 여전히 추가 투자금을 찾느라 시간을 보내는 신진 감독이 늘고 있다. 또 세계 유수 영화제 수상 경력이 있는 유명 감독들도 전주의 투자를 받을 수 있는지 문의하는 일이 잦다. 이는 두 가지를 반증한다. 첫째, 영화가 점점 비싸지고 있다는 것. 둘째, 영화의 역사에 한 획을 그은 작가라 하더라도 투자 지원을 받기가 힘든 현실이라는 것. 신인이든 거장이든, 감독들은 현재 제작비를 구하느라 몇 해씩을 허비하고 있다. 영화를 위해 창의성을 발휘해야 할 시간을 돈을 찾아다니는 데 쓰고 있는 것이다. 이 상황을 돌파할 대안이 있을까?

26회 전주국제영화제 특별전인 ‘가능한 영화를 향하여’는 독립적인 방식으로 꾸준히 영화를 만들고 있는 아홉 팀의 창작자를 소개한다. “작은 영화”라는 고다르의 말에서 시작했지만 특별전에서 주목하는 영화와 창작자 들은 결코 “작은” 존재들이 아니다. 누구나 알 만한 권위 있는 영화제, 즉 칸과 베를린, 베니스, 로카르노 등에 초청되고 종종 수상하기도 하는 이들은 비평가들에게 호평받는 작품들을 꾸준히 내놓고 있다.

잃어버린 감각, 창작의 정신을 찾아서

오스트리아 건축가 아돌프 로스는 『장식과 범죄 Ornament and Crime』(이미선 옮김, 민음사, 2021〔원저 1908〕)에서 오스트리아 수공예 예술이 정체에 빠진 것을 관찰하고 학교도, 산업도 해결 방법을 찾지 못하는 상황에서 다음과 같은 대안을 제시한다. “혁명이란 항상 아래에서 비롯되었다. 그리고 그 ‘아래’란 작업장이다.” 그는 가장 낮은 곳에서 끊임없이 작업을 하며 천편일률적인 배움에서 벗어날 가능성을 모색할 필요가 있다고 강조했다. ‘새로운 정신’은 누군가에게 길들여지고 대중적이 된 무언가에서 나오는 것이 아니라는 것이다.

독립영화를 ‘저예산 영화’라고 착각하는 경우가 많지만, 독립영화는 돈이 없는 영화가 아니라 주체적이고 자율적인 정신을 영화 제작의 핵심에 두는 것을 말한다. 간혹 어떤 프로듀서들은 독립영화를 “상업영화의 연습 과정”이라 치부하며 글로벌 플랫폼에 고용되는 게 창작자로서 가장 큰 성취라는 어리석은 생각을 하기도 하는데, 그렇게 돈과 명성이 모든 것의 중심이 되지 않도록 하는 것이야말로 독립영화의 존재 이유다. 상업영화의 문법을 그대로 차용하지 않고, 다양한 제작 방식과 미학적 가능성을 실험하는 것이다. 최근 독립영화도 상업영화 시스템을 가져와 감독과 프로듀서, 배우 인건비가 전체 예산의 절반가량이 되는 경우가 더러 있다. 그러나 이러한 시스템을 복제하는 것이 단기적으로 생활비를 버는 데 도움이 될 수는 있을지언정 장기적으로 작품을 이어 가고, 독립영화 공동체에 도움이 되는지는 알 수 없다. 이 책에서 소개하는 아르헨티나의 엘팜페로시네는 공동체 형태로 영화를 만들고, 거기에서 생긴 수익은 모든 스태프가 공평하게 나누고 다음 영화를 위해 사용한다. 혹은 테드 펜트, 니콜라스 페레다처럼 자신이 생계를 위해 번 돈으로 스태프에게 소정의 비용을 지급하는 이들도 있다. 누군가에게 지불할 돈이 넉넉지 않은 마리 로지에와 트래비스 윌커슨, 데클런 클라크, 제작사 사랑하자는 그러하기에 본인들이 모든 일을 도맡아 한다. 심지어 라두 주데는 〈잠 #2 Sleep #2〉(2024)에서 ‘데스크톱 필름’이라는 형식을 통해 방 밖을 나가지 않고도 영화를 만들 수 있음을 보여 주었다.

영화와 자본을 나란히 놓고 생각하는 우리의 상식에 제동을 거는 경우는 또 있다. 일례로 라틴아메리카의 경우 국가 경제가 좋지 않은 상황에서도 독립영화가 매우 다양하고 창의적인 방식으로 제작돼 세계 주요 영화제에서 소개된다. 이들에게서 발견되는 특이점은 주로 친구로 이루어진 소규모 그룹으로 일을 하고, 개인적인 이야기에서 출발한 영화를 만든다는 것이다. 또 이들은 현재의 사회·정치에 대해 발언하고, 또 다른 방식의 영화 언어로 자유롭게 표현하는 실험을 주저하지 않는다. 친구들로 스태프를 꾸렸다고 해서 이 영화들이 ‘아마추어 영화’인 것은 아니다. 이들이 가진 것은 ‘아마추어 정신’이다. 이 둘은 완전히 다른데, 요나스 메카스는 아마추어 정신에 관해 아래와 같이 말한 바 있다.

“관습적이고, 생명을 다한, 전형적인 영화에서 벗어나는 것은 건강한 신호입니다. 우리는 덜 완벽하고 그러나 더 자유로운 영화가 필요합니다. 젊은 영화인들이 —저는 구세대에 대한 희망이 없습니다— 진정으로 완전히 힘을 빼고, 거칠고 무질서하게 스스로로부터 벗어나기를 바랍니다! 공식적인 영화의 감각을 완전히 어지럽히는 것 외에는 얼어붙은 영화 관습을 깨는 다른 방법은 없습니다.”

아마추어 정신은 어딘가에 매여 있지 않은 자유로운 정신이다. 자본에 구속되지 않는 것이며, 남들이 정한 규칙과 공식적인 영화 문법을 따르지 않고 인정과 속도 경쟁에서 벗어나 자신만의 비전을 구현하겠다는 헌신이다. 다른 선택을 하고, 다르게 해석하는 행위가 곧 변혁이듯 지금 한국영화에 가장 필요한 것은 ‘생각의 혁명’일지도 모른다.

온당한 불온을 향해

1990년대 ‘코리안 뉴웨이브’가 부상하며 이후 10여 년간 한국 감독들은 세계적으로 큰 명성을 얻었다. 이때 등장한 박찬욱, 봉준호, 김지운 등은 기존과는 다른 새로운 형태의 한국영화를 선보였다. 또 같은 시기 한국영화는 할리우드 블록버스터와 경쟁할 만큼 강력한 산업 시스템을 구축하며 전 세계의 부러움과 찬사를 얻기도 했다. 앞서 언급한 세 감독을 비롯해 당시 등장한 감독 중 일부는 오늘날에도 활발히 활동하며 대규모 예산이 투입된 영화를 만들고, 주요 국제영화제에 소개되기도 한다. 하지만 성공에는 항상 그 이면이 존재하듯, 당시 등장한 독립영화 감독 다수는 영화계에서 제대로 자리 잡지 못했다. 한국 독립영화계에서 재능 있는 감독들은 꾸준히 발견되었지만 자신의 목소리를 내며 지속적으로 작업을 하는 경우는 손에 꼽을 정도다. 홍상수 감독의 경우 ‘작가’로 먼저 자리를 잡은 후 소규모 예산으로 영화를 만들고 있기에 매우 특별한 예외 사례로 보아야 한다.

이제 한국 영화계에서는 감독이 경력을 이어 가는 것보다 첫 장편을 만드는 게 더 쉬운 상황이 되었다. 영화산업이 몸집을 불리며 영화 제작 비용 역시 덩달아 높아졌고, 독립영화도 예외는 아니다. 제작뿐 아니라 배급도 비슷한 상황이다. 영화제를 제외하면 독립영화가 상영될 수 있는 공간은 점점 줄어들고 있다. 이와 같은 영화계의 변화 속에서 전주국제영화제의 고민도 커졌다. 물론 한 영화제가 이 모든 복잡한 정황이 얽힌 문제를 해결할 수는 없을 것이다. 더욱이 영화제와 마켓도 앞서 언급한 문제의 한 부분이자 문제 원인 중 하나일 수 있다. 전주국제영화제에서 산업 행사를 처음 시작한 스태프 중 한 사람으로서, 또 영화제 프로그래머로 7년을 보낸 지금에야 드는 생각은 멘토링 프로그램이 영화 작가를 길러 내는 데 과연 도움이 되는가 하는 의문이다. 멘토링은 필연적으로 산업이나 영화제 시스템에서 통용되는 방식에 맞춤한 영화로 기능할 수 있도록 그 틀 안에서 조언이 이루어지기 때문이다. 즉, 이것이 기존에 있던 영화와 비슷하거나 평균적인 수준의 영화가 나오도록 하는 게 아닌가 하는 고민을 하게 되었다. 골방에서 혼자 글을 쓰고 편집하는 영화인들이 공동체를 경험하는 것은 좋은 일이지만 그 과정에서 독특함을 잃지 않도록, 안전한 영화가 아닌 불온한 영화를 만들도록 독려하는 방법은 없을까. 그러기 위해선 창작자가 온전히 독립적인 정신을 가져야만 한다.

창작의 기쁨을 누려라

올해 베를린국제영화제에서 〈콘티넨탈 ’25 Kontinental ’25〉(2025)로 은곰상 각본상을 수상한 라두 주데는 소감에서 『루이스 부뉴엘 – 마지막 숨결』(루이스 부뉴엘 지음, 이윤영 옮김, 을유문화사, 2021)에 나오는 니컬러스 레이의 사례를 언급했다.

“여기 오는 길에 인터넷을 열었더니 오늘이 루이스 부뉴엘이 태어난 지 125년이 되는 날이더군요. 이 상을 그의 유산으로 여기고 싶은데, 일종의 불경한 유산이겠죠? 오늘 자리를 빌려 그에 관한 일화를 들려 드리고 싶습니다. 부뉴엘의 자서전과, 페드루 코스타의 영화 중 장마리 스트라우브와 다니엘 위예가 등장하는 〈당신의 숨겨진 미소는 어디에? Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie?〉(티에리 루나스 공동 연출, 2001)에도 나오는 이야기입니다. 부뉴엘이 니컬러스 레이 감독을 만났을 때였어요. 레이가 부뉴엘에게 어떻게 그렇게 적은 예산으로 흥미로운 영화를 만들 수 있느냐고 물었죠. 이에 부뉴엘은 당신은 그간 대형 영화를 만들었으니 이제 저예산으로 영화를 만들면 되겠다고 응답합니다. 그러자 레이는 “할리우드에서는 항상 크게, 더 큰 예산, 더 더 큰 예산으로 만들지 않으면 실패”이기에 그건 불가능한 일이라고 말하죠. 저는 바로 이런 어리석은 논리가 우리가 영화계에서 맞서 싸워야 할 대상이라고 생각합니다.”

영화계에서 독립적인 정신을 가진다는 것은 예산, 스타일과 같은 제작 관습에서 벗어나는 것이다. 라두 주데는 어리석은 고정관념을 벗어던지는 것의 일환으로 작은 영화를 실천한다. 그는 최근작 〈콘티넨탈 ’25〉를 스마트폰으로 찍었다. 그러나 적은 예산으로, 새로운 기술을 활용해 작업했다는 것이 그의 영화를 빛나게 하는 유일한 요소는 아니다. 물론 새로운 촬영 방식으로 인한 여러 기술적인 시도가 있었겠지만 여기에 방점을 두지 않는다. 일례로 틱톡의 세로 화면은 회화에서 화면비를 실험하며 과거부터 존재해 온 양식이고, 온라인 숏폼은 숏–리버스 숏과 빠른 속도로 변화를 준 것이지 또 다른 영상미를 보여 주는 건 아니다. 대신 그는 틱톡이나 소셜 미디어를 이야기 안으로 끌어와 서사 방식의 하나로 사용하면서 몇 해 전만 해도 낯설던 온라인 플랫폼이 어느새 우리 일상에 보편적인 커뮤니케이션 방식으로 자리 잡았음을 드러낸다. 라두 주데는 현재의 기술을 사용하되 이를 형식적인 틀로만 이용하지 않고 주제와 연결하며 동시대의 새로운 영화 언어로 승화하였다.

가상 현실, 인공지능 등 최근 걷잡을 수 없이 빠른 속도로 발전하고 있는 기술은 영화계에도 영향을 미치고 있다. 하지만 라두 주데의 경우로 살펴본 것처럼 최소한 문화 영역에서의 기술 발전은 문화와 예술의 콘셉트를 중심으로 논의되어야 한다. 즉 이들은 도구이지 정신이 될 수는 없다.

라두 주데를 비롯해 이번 특별전에서 소개하는 창작자들은 현재의 영화 기술을 영화 미학으로 적용해 내는 저돌성과 단호함을 보여 준다. 또 다른 공통점도 많다. 첫째, 이들은 영화 제작에 있어 절대적인 독립성을 유지한다. 둘째, 작가로서 자신만의 작업 스타일을 구축해 영화계에 표식을 남겼다. 셋째, 다작을 한다. 즉 이들은 외부 프로듀서를 찾거나 돈을 기다리며 시간을 허비하는 대신 자신의 작업과 예술을 추구하면서 얻는 기쁨을 분명히 표현하는 진정한 필름 메이커들이다. 마지막으로 어쩌면 가장 중요할지도 모를 공통점은 다음과 같다. 이들 모두 필모그래피가 쌓이면서 자신만의 독특한 스타일을 개발한 동시에 영화의 미학(aesthetics, 우리가 보는 것)과 제작 윤리(ethics, 제작 방식)를 같이 고민하는 이들이라는 점이다. 이들은 영화를 통해 우리가 살고 있는 시대와 자신들이 영화를 이해하는 방식에 관해 함께 이야기하는 ‘작가’들이다. 언뜻 이것은 아주 단순해 보이지만 영화계, 나아가 예술계 전반이 잊고 있는 부분이라는 점에서 중요하다. 이들이 고수하고 있는 지속 가능한 영화의 스타일과 이를 현실화하는 제작 방식, 그들의 생각이 모두 자신들의 삶과 연결되어 있다는 점은 일견 존경스럽기까지 하다.

작은 영화를 통한 창작의 경쾌함과 순수함을 강조하는 예는 역사 속에서 진정한 예술가들에 의해 지속되어 왔다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이 말들의 중요성은 여전히 소수에게만 들린다는 역설 속에 역사는 반복된다. 심지어 우리는 최근 오스카 시상식을 통해 독립영화가 스튜디오들이 구매하고, 브랜드로 내세울 수 있는 무언가가 되어 버린 것을 목격할 수 있었다. 이번 특별전에서 소개하는 영화와 창작자 들이 영화계가 마주하고 있는 수많은 문제에 정답을 제시할 수는 없을 것이다. 그러나 현실의 벽에 부딪혀 창작을 머뭇대는 이들에게 충분한 대안이 될 수 있는 것도 맞다. 여러 이유로 계속해서 외곽으로 밀려나고 있는 ‘다른 생각’ 혹은 ‘다른 방법을 상상하는 힘’이 사실은 창작의 기본 바탕이라는 것을, 우리는 각자 처한 상황을 예술적 돌파구로 헤쳐 나가는 이들을 통해서 배울 수 있다.

남미 안데스 지방 원주민들에게 전해지는 옛 이야기가 있다. 산불로 덩치 큰 동물들이 모두 도망을 갈 때 작은 벌새 한 마리가 주둥이에 물을 담아 와 불을 끄려 노력하며 “나는 내가 할 수 있는 일을 할 뿐”이라고 했다는 것이다. ‘가능한 영화’를 통해 자신이 할 수 있는 최선을 다하는 창작자들의 정신을, 벌새의 힘찬 날개짓에 담아 보낸다.

고독의 오후 Afternoons of Solitude 감독 알베르 세라 Albert SERRA | Spain, France, Portugal | 2024 | 126min | Documentary | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

가끔 구름 Can We Just Love 감독 박송열 PARK Songyeol | Korea | 2018 | 71min | Fiction | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

낮에는 덥고 밤에는 춥고 Hot in Day, Cold at Night 감독 박송열 PARK Songyeol | Korea | 2021 | 90min | Fiction | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

내가 넘어져도 내버려 둬 If I Fall, Don't Pick Me Up 감독 데클런 클라크 Declan CLARKE | Ireland | 2024 | 116min | Experimental | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

밤의 라사로 Lázaro at Night 감독 니콜라스 페레다 Nicolás PEREDA| Mexico, Canada | 2024 | 77min | Fiction | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

몬동고 1: 곡예사 Mondongo I: The Tightrope Walker 감독 마리아노 지나스 Mariano LLINÁS | Argentina | 2024 | 73min | Documentary | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

몬동고 2: 몬동고 초상화 Mondongo II: Portrait of Mondongo 감독 마리아노 지나스 Mariano LLINÁS | Argentina | 2024 | 121min | Documentary | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

몬동고 3: 색채의 예술 Mondongo III: Kunst der Farbe 감독 마리아노 지나스 Mariano LLINÁS | Argentina | 2024 | 90min | Documentary | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

피치는 미쳐 가고 있어 Peaches Goes Bananas 감독 마리 로지에 Marie LOSIER | France, Belgium | 2024 | 74min | Documentary | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

불행한 시간 Unhappy Hour 감독 테드 펜트 Ted FENDT | Germany | 2023 | 10min | Fiction | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

누가 울새를 죽였나? Who Killed Cock Robin? 감독 트래비스 윌커슨 Travis WILKERSON | United States | 2005 | 80min | Fiction | 특별전: 가능한 영화를 향하여 Special Focus: Possible Cinemas

The term “alternative” has been the guiding principle that has defined the JEONJU International Film Festival (JEONJU IFF) for 26 years. Setting “digital” as an alternative to film, the JEONJU IFF centered on “independent cinema” as an alternative to mainstream cinema, and proclaimed “Cinema, Liberated and Expressed” as an alternative to convention. Then what kind of alternative is needed in today’s world of film, where the economic crisis is suffocating culture, cultural policies are being swayed by political circumstances, and the focus is on industries rather than art? This is where the 26th JEONJU IFF’s special exhibition “Special Focus: Possible Cinemas” began.

The special exhibition “Special Focus: Possible Cinemas” introduces 12 films made by 9 creative teams. Featured are another film by Radu JUDE, who directed this year’s opening film, Kontinental ’25, the production company El Pampero Cine, whose director Mariano LLINÁS who has been a long-time subject of attention for JEONJU IFF, and the Korean production company Saranghaja which builds teams that create their own films. We conducted interviews to ask these creators, who prioritize “cinema” in all circumstances, what cinema means to them, how they balance cinema as art and cinema as an industry, and what it is like to live as a filmmaker in this era. These interviews were then published in the book POSSIBLE CINEMAS. Here, programmer Sung Moon, who curated the special exhibition, examines the reality of Korean cinema and conveys the inspiration we can draw from these creators.

A Possible Introduction

“I am interested in making films from a notion of closeness that industrial systems sometimes make difficult. I am interested in working on certain stories, materials, and staging that are not so easy to translate into a dossier and convince large financing structures. Luckily, I like to work economically, in the times that the project needs, and with a group of people who are who they are and not who they should be.” Matías Piñeiro

“What is the spirit ofthe JEONJU International Film Festival, and what should it be?”

This question follows me at every turn—when selecting films for screening or when contemplating the festival’s broader direction. Last year, JEONJU International Film Festival screened Room 666 (Wim Wenders, 1982), a documentary that asked various directors whether they believed cinema was a disappearing art form. In the film, Jean-Luc Godard remarked, “Cinema was born with small movies.” This statement inspired the concept for “Special Focus: Possible Cinemas” for the 26th JEONJU IFF.

What constitutes a “small film” in today’s landscape? The answer spans various dimensions: budget, filming technique, production methodology, or independence from mainstream cinema. Consider Godard himself, who crafted his final works at his home in Rolle, Switzerland, with just a handful of collaborators working on a small scale, almost by hand—perhaps this example could be the answer to our earlier question.

Within the Korean film ecosystem, JEONJU IFF has carved out its identity as the festival championing the most independent cinema. Since 2014, the JEONJU Project has been investing up to KRW 100 million in a feature film annually, and directors are required to complete their work by the following year to be screened at the festival. The initiative, designed to support filmmakers with at least one feature film under their belt and to vitalize low-budget production, has brought thirty-seven films into existence to date. Yet recently, we have noticed an increasing number of emerging directors spending considerable time seeking supplementary funding even after receiving our funding of KRW 100 million. At the same time, we have been receiving more frequent inquiries from acclaimed filmmakers with prestigious festival accolades about our investment. These circumstances reveal two troubling realities—one, films are becoming increasingly expensive to produce, and two, even established auteurs who have made their marks in the history of cinema struggle to secure financial investments. Directors—whether newcomers or masters—waste precious years chasing production funds rather than realizing their creative visions. Then the question becomes: is there a way to breakthrough the current situation?

The 26th JEONJU IFF’s Special Focus: Possible Cinemas showcases nine creative teams who consistently produce films through independent means. Though sparked by Godard’s notion of “small films,” these featured filmmakers are anything but “small.” They routinely receive invitations to—and occasionally win awards at—the world’s most prestigious film festivals like Cannes, Berlin, Venice, and Locarno, creating critically acclaimed works with remarkably consistency.

In Search of Sensibility and Creation

In his book Ornament and Crime (1908), Austrian architect Adolf Loos observed the stagnation of Austrian craft arts, with neither educational institutions nor industry finding viable solutions. His proposed alternative was as follows: “…revolutions always come from below. And that ‘below’ is the workshop.” Loos emphasized the necessity to work continuously at the most fundamental level, exploring possibilities beyond standardized learning. A “new spirit,” he argued, never emerges from something that has been tamed and mainstreamed.

There is a common misconception that independent cinema means “low-budget filmmaking,” but independence in filmmaking is not only about financial constraints—it is about placing autonomous, self-directed creative spirit at the heart of film production. Some producers dismissively regard independent films as merely “practice for commercial cinema,” foolishly suggesting that landing a job with global platforms is a creator’s ultimate achievement. Yet the very essence of independent cinema is its resistance to making money and fame the centerpiece of everything. It is about experimenting with diverse production methods and aesthetic possibilities without simply adopting commercial film grammar. Recently, some independent productions have imported commercial systems, with director, producer, and actor fees consuming nearly half the total budget. While mimicking such systems might help cover living expenses in the short term, it is unclear whether this approach sustains long-term creative work or benefits the broader independent film community. Argentina’s El Pampero Cine, featured in this book, operates as a collective, distributing profits equally among all staff and reinvesting in future projects. Filmmakers like Ted Fendt and Nicolás Pereda pay their crews modest fees from money earned through their day jobs. Others, like Marie Losier, Travis Wilkerson, Declan Clarke, and Saranghaja handle almost everything themselves as they lack sufficient funds to pay others. Radu Jude even demonstrated through Sleep #2 (2024) how one could make a film without leaving his room, using the “desktop film” format.

Other examples also challenge out conventional thinking about film and capital. Despite challenging national economic conditions, Latin American independent cinema flourishes with diversity and creativity on the international film festival circuit. What distinguishes these filmmakers is their tendency to work in tight-knit groups of friends, creating films that spring from personal stories. They boldly comment on contemporary social and political issues and experiment freely with alternative cinematic languages. Though their crews consist of friends, these are not “amateur films”—they embody the “amateur spirit,” which is altogether different. Regarding the “amateur spirit,” Jonas Mekas said:

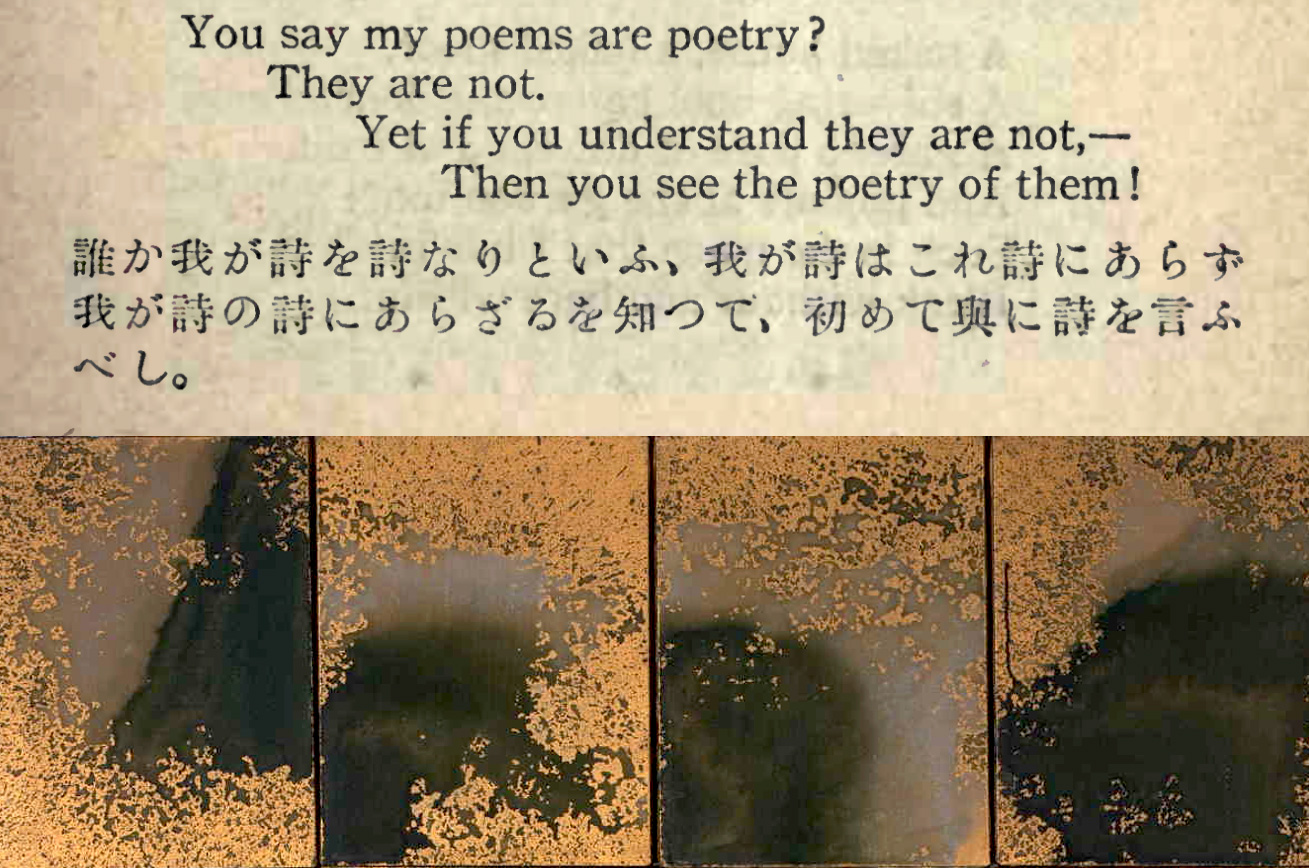

“Every breaking away from the conventional, dead, official cinema is a healthy sign. We need less perfect but more free films. If only our younger film-makers— I have no hopes for the old generation—would really break loose, completely loose, out of themselves, wildly, anarchically! There is no other way to break the frozen cinematic conventions than through a complete derangement of the official cinematic senses.”

The amateur spirit is a free spirit, unbounded by systems or institutions. It means refusing to be constrained by capital, rejecting established rules and formal film grammar, and committing to realize one’s vision outside the race for recognition and speed. Just as making different choices and interpretations constitutes transformation, perhaps what Korean cinema needs most today is a revolution in thinking.

Toward a Proper Impropriety

The emergence of the Korean New Wave in the 1990s catapulted Korean filmmakers into the global spotlight for over a decade. Directors who rose to prominence, such as Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Kim Jee-woon, introduced radically new forms of Korean cinema. During this same period, the Korean film industry built a formidable system capable of going toe-to-toe with Hollywood blockbusters, earning admiration and envy of the world. Some directors from this era, including the three mentioned above, remain at the forefront of the industry, working on big-budget productions that premiere at prestigious international film festivals. But as with any success story, there is a shadow side: many independent filmmakers who emerged during this period never gained a foothold in the industry. While the Korean independent film scene has consistently discovered talented directors, there are only a handful of those who maintain their distinctive voice while sustaining ongoing work. Director Hong Sang-soo stands as a remarkable exception, as he first cemented his reputation as an auteur before shifting to small-budget filmmaking.

In today’s Korean film scene, making a debut feature has become easier than sustaining a directorial career. As the industry has expanded, production costs have skyrocketed across the board, and independent cinema is no exception. Distribution faces similar challenges. Aside from film festivals, screening venues for independent films continue to diminish. Amid such shifts in the industry, the concerns facing JEONJU IFF have only deepened. No single film festival can untangle all these complex, interconnected problems, of course. In fact, festivals and markets may themselves be contributing factors to this problem. As one of the original staff who launched industry events at JEONJU IFF, and now after seven years as the festival’s programmer, I have begun questioning whether mentoring programs genuinely nurture original filmmakers. Such mentoring inevitably dispenses advice within frameworks designed to conform to industry standards and festival expectations. This has led me to wonder whether these programs simply yield films that are similar to existing works or produce merely average works. While filmmakers who write and edit in isolation certainly can benefit from community experience, how can we encourage them to preserve their uniqueness in the process and create improper and provocative films? To achieve this, creators must embrace a truly independent spirit.

In Pursuit of Creation

At this year’s Berlinale, Radu Jude, who won the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay for Kontinental ’25 (2025), mentioned Nicholas Ray in his acceptance speech, drawing from Luis Buñuel’s memoir My Last Breath:

“Before coming here, I opened the internet…and I observed today is 125 years since Luis Buñuel was born. Allow me to dedicate this award to his legacy, which is the legacy of irreverence first of all I think, and to tell you a small anecdote you can find in his autobiography and in the great Pedro Costa film about Straub [Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet in Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie? (2001)]

At some point Buñuel met Nicolas Ray, and Nicolas Ray said to Buñuel how great it is you can make these cheap movies. Buñuel said you made a big production, now you can make a cheap film yourself. And he said no, no, no, that’s impossible because in Hollywood you have to go always with bigger budget, bigger budget, bigger budget - so it’s impossible. Well, I think that’s the thing we have to fight in cinema against this stupid logic.”

Having an independent spirit in filmmaking means breaking from production conventions around budgets and style. Radu Jude embodies this spirit of making small films by rejecting foolish industry stereotypes. He shot his latest film Kontinental ’25 entirely on a smartphone. However, working with a modest budget and utilizing new technology is not the only thing that makes his films shine. While his approach certainly involved various technical experimentation, he does not foreground this aspect. TikTok’s vertical format, for instance, has existed in painting for centuries as part of aspect ratio experiments, and online short-form videos merely applies traditional shot-reverse-shot techniques at a faster pace rather than creating a new visual aesthetic. Instead, Jude weaves TikTok and social media into his narrative framework, highlighting how platforms that seemed alien just a few years ago have become everyday communication tools. He employs contemporary technology not as mere formal device but as a thematic element, creating a new cinematic language for our time.

The rapidly advancing technologies of virtual reality and artificial intelligence are undeniably influencing filmmaking. However, as Jude’s case demonstrates, technological developments in cultural sphere should be discussed primarily through the lens of cultural and artistic concepts. These technologies are tools, not the driving spirit.

The creators featured in this year’s Special Focus, including Jude, display boldness and determination in applying current technologies to cinematic aesthetics. They also share several other commonalities: they maintain absolute independence in production; they have established distinct styles as auteurs, leaving their mark on the film industry; and they are prolific. Rather than wasting years seeking external producers or waiting for funding, these genuine filmmakers openly express the joy they find in pursuing art and their craft. Perhaps most importantly, they share this last commonality: as their body of work has grown, they have developed unique styles while simultaneously considering both film aesthetics (what we see) and production ethics (how films are made). They are auteurs, who, through their work, engage in dialogue about our times and their understanding of cinema. While this may seem straightforward, it has significance importance, as it represents something the film industry—and the broader art world—has largely forgotten. Their commitment to sustainable filmmaking, production methods for realizing their visions, and the integration of their ideas with their lives is genuinely admirable.

Throughout history, true artists have championed the lightness and purity of creation through small films. Yet, paradoxically, this message continues to reach only a select few. We have witnessed independent films becoming commodities that studios purchase and showcase as brands, as made painfully clear by the recent Academy Awards. The films and creators featured in this year’s Special Focus may not offer definitive answers to the numerous challenges facing the film industry. However, the provide viable alternatives for those hesitating to create films due to real-world obstacles. From these artists who transform their circumstances into artistic breakthroughs, we learn that “different thinking” or the “power to imagine alternative methods”—though increasingly marginalized for various reasons—forms the essential foundation of creative work.

There is an old story passed down among indigenous peoples of the South American Andes: when a forest fire broke out and all the large animals fled, a tiny hummingbird carried water in its beak, trying to extinguish the flames, saying, “I’m simply doing what I can.” Through “Possible Cinemas,” we celebrate the spirit of creators who do their utmost, carried forward on the vigorous wings of the hummingbird.