감독 그레이엄 하이드 Graham HEID, 윌프레드 잭슨 Wilfred JACKSON | United States | 1937 | 9min | Animation | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU

If an animal could understand human language literally (rather than in terms of tone, temperature, pitch…) many expressions commonly used by filmmakers would certainly evoke fear or dread. Directors regularly speak, for example, of “shooting” a film and “capturing” footage of their subject, expressions that directly imitate the language of the hunt—of a human armed (in this case, with a camera) chasing after prey. Across its long and rich history, the relation of the cinema to animal has remained tethered to this idea of the hunt, to animals being chased, caught and “preserved” in a form of moving image taxidermy. Indeed, the history of cinema began, it could be argued, with a man and a camera aimed at an animal- the man was Eadweard Muybridge and the man was a horse. As a result, the default position throughout film history is to treat animals as subjects captured for specific scientific, aesthetic and narrative purposes.

This series of films offers three alternate, generative counter-positions taken by filmmakers towards animals, each from distinct historic periods and national cinemas. While this program’s films each reflect their respective culture’s distinct attitudes towards animals and nature in general, they cannot, however, simply be reduced to only a product of the time and time and place of their creation. Instead, the three films connect across film history to forge an inquisitive and progressive dialogue about animal agency and the limits of human and cinematic understanding. Ranging from popular animation, to religious allegory, to art house slow cinema, the three films nevertheless speak as well to different ways that animals continue to serve primarily as narrative devices- as (unpaid) actors of sorts asked to do the hard labor of carrying a film forward and engaging the audience.

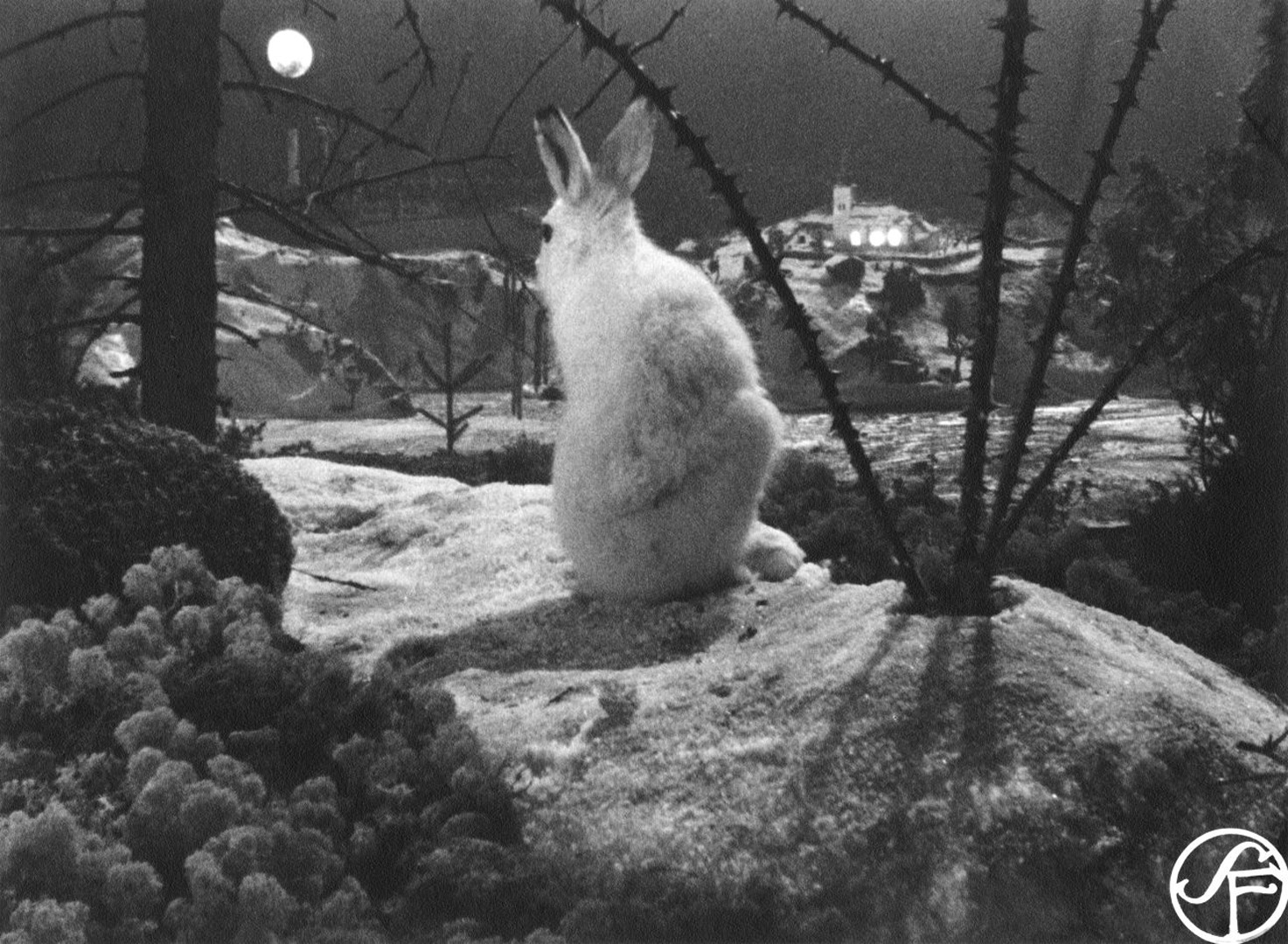

A favorite of Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, Walt Disney’s innovative late entry in its popular Silly Symphony series, The Old Mill (1937) imagines animals in a world without humans, reinventing through habitation the proto-anthropocene space of the abandoned eponymous mill. In contrast, pioneering Swedish documentarian Arne Sucksdorff’s stark and mesmerizing short A Divided World (1948) keeps humans at a measured distanced, again marked by a building but this time a church animated with holy music and the effulgent glow through its windows. Here the animals are still independent but seemingly judged as mortal and possibly moral creatures. In the third and most recent film in this program, The Four Times (2010) Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Frammartino man and animal are brought together into a slow dance that traces the longue durée of cyclical time of animal and human labor as synched to and working at the service of the same infinitely patient clock. In this film the human and animal world are given a rare symmetry and equity, as musically and metaphysically one.

This program brings together three beautiful vintage 35mm prints from the Harvard Film Archive in order to showcase the distinctly qualities of the organic, photochemical moving image and medium, so much closer to the natural world of the very animals to which they give precious life.

감독 아르네 숙스도르프 Arne SUCKSDORFF | Sweden | 1948 | 8min | Documantary | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU

감독 미켈란젤로 프라마르티노 Michelangelo FRAMMARTINO | Italy, Germany, Switzerland | 2010 | 88min | Fiction | 시네필전주 Cinephile JEONJU