Bill Mousoulis and Margot Nash are among the most prominent and beloved independent filmmakers in Australia. They belong to different generations: Margot was part of the countercultural, feminist and collective movements of the 1970s, while Bill emerged in the ‘postmodern’ scene of artistic Super-8 filmmaking. Their aesthetics are quite distinct but, over time, their career paths have more closely come to resemble each other. Both of them are explorers of possibilities: possible ways of financing and making films across the contexts of changing times, and possible ways of approaching personal, often challenging themes and ideas. Their films are characterised by bold uses of cinematic style – from the tersely minimal to the highly lyrical – and by a commitment to personal, intimate expression within and against the prevailing social framework. They are both closely involved with the broader film culture of Australia: research, writing, teaching, the curating and presenting of films to the public, distribution, militating for better cultural conditions and economic opportunities for independent filmmakers. In short, Margot Nash and Bill Mousoulis are an essential part of the lifeblood of a still-vital Australian cinema today.

What was the trigger in your life that impelled you into filmmaking?

MARGOT NASH In 1972 I was an in-and-out-of-work actor, sharing a house with my friend, Robin Laurie, who was teaching Super-8 filmmaking at Melbourne University. She had been active in the Melbourne University Film Society (MUFS), and would sometimes bring home a 16mm film projector and project European art films on the lounge room wall. I had never seen films like that before. We started ‘talking film’ and decided to make a film together. We wrote a script and successfully applied for $1,300 from the Experimental Film Fund. This film would eventually become We Aim To Please (Robin Laurie & Margot Nash, 1976). I had started working as a camera assistant and would bring camera equipment home on weekends to film. We had abandoned the script and instead began to film new ideas. I edited it in my bedroom on an old hand-wound, ‘pic sync’ and, in the process, fell in love with film and the magic of putting sound and image together. Jean-Luc Godard’s Two Or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) which I saw on someone else’s loungeroom wall, and Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)which I saw at the Melbourne Filmmakers Co-op, had a major impact on me during this time.

BILL MOUSOULIS When I was a teenager, films meant very little to me – more important were music and comic books. As a 15-year-old I started writing songs and recording them in a very lo-fi way, with my cousin. This was an outlet for what was obviously a creative urge in me. Shoot forward to the age of 18 and I became a rebel to my family, refusing to go to university to study for a professional career in medicine or law (the expected thing for a child of Greek migrant parents). Instead, I stayed home all year and started watching films on the TV, and very quickly I was struck by their artistry. From early Frank Capra films (pre Hays code), to classic Hollywood films (Ford, Hawks), to European auteurs (Renoir, Bergman – yes, commercial TV in 1982 still had some quality on it), I was immediately smitten by cinema and its riches. Halfway through that year, I thought to myself – “I wonder if I also can make a film?” I answered categorically in the positive, and so my creative urge now had a new form, and one that has lasted so far to this day, 43 years later.

I regard you both as independent filmmakers. What does that label mean to you, in relation to your artistic creativity, and to the practicalities of production?

BILL Yes, I label myself an ‘independent filmmaker’, but I don’t necessarily see that as a position completely away from or antagonistic to the mainstream/arthouse industry or film marketplace. For myself, the main thing when I started was to come up with original ideas, ones I valued and cherished even, and then secondly to find the means to realise them. In my first few years (of which the short film Dreams Never End, in the Jeonju program, was a product), I truly was completely independent, as I didn’t go to any film school and had no access to any money from any source to make my films. I saw that Super-8 cameras were being sold in camera stores, so I bought one, and my first few films, from 1982 to 1984, were made solely by myself, using friends and family and relatives as actors (my sister, for example, in Dreams Never End). After that, I received government funding for some short films and feature-length scripts. Eventually however, starting from around 2000, the Australian film ecosystem stopped valuing more artistic projects, and the funds stopped flowing to the more alternative filmmakers. So, in recent years, I now simply make films with my own money. If I had lived my life in Europe or Asia or even North America, I would have been more supported by the ‘industry’ and made films with more money (but with the condition of course of always retaining artistic and my own individual integrity).

MARGOT For me, being an independent filmmaker essentially means working outside the system. Creatively, it means feeling free to push boundaries, and experiment with radical ideas, both artistically and politically, without the pressure to make something commercial. In America, ‘the system’ means the Hollywood studio system, which we do not have in Australia, but also other corporate systems such as television. While independent filmmakers in Australia are ‘independent’ in so far as they do not have to answer to studio executives, most of us have been dependent on finance from government funding bodies, with their increasingly risk-averse agendas and focus on market viability. Filmmaking is expensive, even using cheap digital technology, and raising finance for films has become extremely competitive, leading to more and more control being exercised by the funding bodies over who, and what, gets funded, and how the money is spent. The 1970s days of the Experimental Film Fund are well and truly over and ‘the market’ rules. These days, the only truly independent films are low-budget, self-funded films that rely on personal savings, crowd funding or philanthropic sources.

I also see the two of you as ‘survivors’, still making work today and getting it out there for audiences to see and experience. Yet you have undoubtedly experienced frustrations (unmade projects, etc.) and lulls in your career. Many independent filmmakers give up along the way, and often for quite understandable, valid reasons. What are the convictions and conditions that have kept you going ‘in the game’ all this time?

BILL What drives people like Margot and myself? Indeed, there is a great drive, almost a compulsion, to make films and to continue to make them. It goes to existential and philosophical questions, of course (and psychological ones, too). I agree with Nietzsche’s dictum that “Art is the salvation of life”, no matter how dramatic that may sound. As many artists have said about themselves, I wouldn’t know what else to do with my life that would still give me the deep fulfilment that cinema gives me. Yes, I have experienced setbacks and frustrations in my film career (or passion, let’s call it), including a short period of depression I had when I was in my mid-30s, but the absolute joy and fulfilment that cinema gives me always keeps me loving it.

MARGOT I love making films. Even when a major project fell over some years ago, and I had to put my head down and teach in order to survive and have somewhere to live, I still made films. Small projects that I edited and gave to my family, or extended family, celebrating the achievements of others, birthdays or the lives of loved ones who had died. These home movies kept my itchy editing fingers happy and gave me pleasure to produce. During this time, I wrote a number of feature length screenplays that were not produced, but each unproduced screenplay increased my skills and taught me something new. In the 18 years of teaching at the university, I only managed to make two major films, Call Me Mum (2005) and The Silences (2015), that had a public life on the film festival circuit and in the cinema. I took six months’ leave to make the first one and the second was developed through an international artist residency, where I took a semester off from teaching. Long enough to get the project going, but it took another three years to complete the film. Teaching meant most of my creative energy went into nurturing the creativity of others but, as soon as I retired, I started making films again. My short film Undercurrents: Meditations on Power (2023), screening at Jeonju, was self-funded and made by reimaging or recycling images and sounds from my previous film work. I didn’t even try to get funding, as I knew it would not ‘tick the boxes’. I just did it because I had something to say, and I could.

I interpret both of your careers as distinct, individual manifestations of that great 1970s slogan, ‘the personal is political’. How do you conceive of the interplay between personal life and political issues in your work? How does that dialogue of personal and political express itself?

MARGOT I associate ‘the personal is political’ with feminism. As young feminists in the 1970s, we learned that the experiences of women were undervalued and often written out of history, regardless of class. Women’s desires and women’s struggles against injustice had been repressed or trivialised, and images of women in the media were passive and sexually pliant in order to serve the interests of male desire. We learned that our personal experiences of discrimination and isolation were shared by other women. We were not alone, and to speak publicly about this, and make films about it, was political. I began to make feminist films, often collaboratively, which spoke about the gaps or silences in history, and about repressed female desire. ‘The personal is political’ was also used in the civil rights movement, and other social movements, where the experiences of individuals had been undermined and repressed by the dominant social system in order to crush dissent and consolidate power. ‘The personal is political’ directly connects personal experience with a critique of wider social structures of power. Not all my films are about my personal experiences, but all my films explore this concept.

BILL Yes, everything is political ultimately, or maybe we could say it’s philosophical or ideological, the term doesn’t matter that much. Margot’s career, more than mine, is more political in the literal sense of the word, with her rich history of anarchist and feminist activity, connecting to her film work and cultural work. Indeed, apart from being filmmakers ourselves, Margot and I have been very enmeshed in film cultural work over the years (film co-operatives, magazines, curating screenings, etc.). But, getting back to the personal and the political as expressed in our actual film work, yes, there is a dialogue there. For myself, the content and themes of my work (apart from the overtly political phase I had when making films in Greece between 2009 and 2017) are political in the way I highlight the human condition (between the poles of love and murder), as opposed to doing genre work for example. There is a humanitarianism involved and invested in these tales of desire and dejection that I have made. In a way, these themes are no different from feminist or queer themes for example – everything ultimately goes back to the matter and experience of being human, the upholding of human rights and the individual predilections of each human. And this also connects to the film cultural work Margot and I do and have done, as we always seek to value and promote the marginalised or alternative filmmakers in the Australian scene.

Much mainstream Australian cinema (with some excellent exceptions, of course) cares more about ‘content’ (plot, characters, acting, setting) than about fine-grain matters of ‘form’ or filmic language. And the mainstream cares even less about intellectual ideas, film theory, and the newer styles of film criticism that have flourished since the 1970s in places like the Australian publications Filmnews and Senses of Cinema – all of which it regards as largely esoteric and irrelevant to the business of making films. What’s your own awareness of film form, how do you work with that? And how does the culture of serious film discussion affect or influence you?

BILL You said it, brother. Firstly, there was a period in the early 1970s where the burgeoning Australian filmmaking scene was just finding its feet, it was hovering between the crazy independent films being made at the time, the bawdy comedies, and the middle-brow arthouse films coming into vogue. These forks were dissolved quickly though, as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) lead Australia down the safe, well-trodden path of the middle-brow, ‘cinema of quality’ film. Since then, the divide between the independent/alternative (and intellectually rigorous) film world and the mainstream film world has been widening and widening, to the point where now, in 2025, Australian mainstream cinema has little value (or estimation worldwide). In my own film work, I’ve always considered myself realist and humanist, but also formalist – all three being equally as important. Which is not to say that these three modes have been necessarily in balance in my films, as some of my films are more experimental than others, some are fiction, some documentary, some essay, there is a huge eclecticism to my work. And whilst the themes are important, really, cinema is form, fully it is form. As for serious film discussion, even though I myself am not an academic or intellectual person, I have always been inspired by film criticism, especially certain critics (like yourself Adrian, or John Flaus for example) who have individual passion and always say interesting things about the films they are discussing. The criticism then inspires my own film work. I guess it should also be noted that I myself founded the online journal Senses of Cinema in 1999 (still running today), so obviously I value criticism quite a lot.

MARGOT When Robin Laurie and I made our wicked little experimental film about female sexuality, We Aim To Please, we had not read Laura Mulvey’s seminal theoretical work about the representation of women, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975). If we had, I suspect we would have been too scared to make it for fear of doing the wrong thing! We were reading a lot of feminist theory, yet interestingly, it was John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) that directly influenced us in terms of the visual representation of women and the male gaze. Also Godard, who cheerfully broke the fourth wall and gave us permission to experiment with film form, in particular the direct address. As I became more engaged with filmmaking, the culture of film theory played a bigger role. I found it challenging and intellectually stimulating to explore different ways to understand, the way film worked culturally to support the current systems of power. Drawing on philosophy, and psychoanalysis, the new wave of film theorists challenged us to try and find different forms that might break through those systems of power, and create new ways of seeing. However, theory and practice are different and the creative process means ‘freefalling into the unknown’, with intuition rather than logic as guide. It’s a mysterious space, and one where theory can get in the way. I have never wanted to make conventional films, but I spent many years teaching screenwriting, so I had to teach the basics of structure, character, plot and mise en scène. But I also investigated, and taught, the way some of the more interesting filmmakers reimagined the conventions and experimented with film form.

You have both been involved in a range of activities that we can put under the broad umbrella of ‘film culture’, from teaching and film distribution/exhibition to critical writing and promotion of Australian independent cinema. You’ve both been part of ‘collective experiences’ such as feminist groups, the filmmakers’ co-operatives, or the Super-8 movement. What’s the importance and necessity of that kind of activity for you?

MARGOT I think being part of collectives and other groups helps you find your ‘tribe’, your community. Like any artist, being an independent filmmaker can be lonely, and being part of a wider group can create a sense of belonging. Many friends I made back in the early days are still my friends and colleagues, and I value those connections. I was involved with the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op, which was started in the 1970s by the Ubu film group, who wanted to get their films seen and distributed. Up until then, conventional wisdom had been that there wasn’t an audience for experimental films like this, or for Indigenous, feminist or political documentaries. The Co-op proved this wrong. I used to work there cleaning 16mm films that might have come back from schools, trade unions and universities or from the central desert with insects still stuck to them. We had an Aboriginal ‘Black Film Worker’ who put Indigenous films in the back of a station wagon with a projector and took them out to remote communities. We had a small cinema in inner-city Sydney and a newspaper called Filmnews, where our films could be reviewed, discussed and advertised. Films are made to be seen and engaged with, and being part of activities like the promotion of film and film culture is critical for independent filmmakers if they want to stay informed, as well as get their films out. It was only after I became an academic that I began researching and writing about film. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed this. I have published about creativity and the uncertain nature of film development, adaptation, subtext, the work of other filmmakers, and women filmmakers in the silent era in Australia.

BILL Yes, it’s quite remarkable that both Margot and I have been attracted to this film-cultural side of things. We could have easily just concentrated on our film work (like most filmmakers), and become ‘mad artists’, but we have both chosen, in different cities, to be involved in the film-cultural scene. For me, it’s the love of cinema that has created this. Loving cinema fully means loving every aspect of it (within the alternative sphere, not the mainstream one). Whilst I still believe films themselves are the most important things, the ‘primary objects’ of all the activity around them, all that activity (promotion, discussion) around them is still crucial, if for no other reason than to just make those films available, for people to watch and enjoy and talk about them. And this is clearly tied to the realm of the alternative – the political filmmaker, the underdog filmmaker, the surreal filmmaker. The mainstream world, especially in Australia, is limited to what’s in vogue and what’s commercial. And the film funding organisations in Australia these days (as opposed to a few decades back) have little money for film cultural activities, especially those revolving around the alternative or the historical, so a lot of this activity is also DIY, low-budget, hand-made. So, for Australian independent cinema, I create websites and organise screenings, all for no money whatsoever, or with help from the community of ‘indie’ filmmakers themselves.

Since the 1970s for Margot and since the 1980s for Bill, you have both traversed – like many independent filmmakers – many different technical formats and gauges: Super-8, 16mm, 35mm, digital, a film for TV – and also diverse genres of documentary, fiction, experimental, personal essay, and so on. Do you feel, now in this almost all-digital point of the 21st century, that you’ve ‘arrived’ or ‘settled’ anywhere in your practice, or does the restless search for expression continue?

BILL The restless search for expression continues, for sure. The technology is always changing, but that’s okay, that’s natural. I prefer the film gauges, but these days, in the 2020s, digital cinema looks pretty good, compared to its early days of the ‘90s and ‘00s. In any case, as independent filmmakers, we use the technology we can afford or have access to, because the desire to make films outstrips these more superficial questions of gauge. In terms of genres or forms, however, if one settles, one is lost. In a way, for my first 25 years of making films, yes, there was, within my feature or narrative film work, a practice where I was doing ‘variations on a theme’ (or a form/style) – mainly European-influenced, austere art cinema work around themes of love, murder, desire. After that, in my time in Greece, I made the two features Wild and Precious (2012) and Songs of Revolution (2017) that are mainly documentaries, and political ones at that. And more recently, my feature My Darling in Stirling (2023) is a genre film, a musical, and I am planning another genre-type feature next. It must also be noted that apart from these 11 features I have made, there have been over 100 shorts, too, over the years, and they are very eclectic, playful, experimental.

MARGOT I think the restless search for expression continues, particularly as it is so difficult to raise money to make films that do not follow the risk-averse, market-driven development process advocated by the funding bodies. I prefer a discovery-driven process, which is the way many visual artists work. Artists can raise money for a creative development process to explore ideas, but filmmakers have to plot out a film, like a blueprint, before getting money to even develop an idea, much less produce a film. This is why I try to stay away from the funding bodies, and have recently explored a low budget way of working with my own archive in the editing room. Everything is digital now, and we are so used to HD that archival materials need restoring or digitising to HD to use them. Most of my films have now been digitally restored, which has given them a new life in film festival restoration programs, but it has also meant they are available to me to work with in the editing room to produce new work. I have digitised all my Super 8 as well as my 16mm films. I used clips from my restored feature drama Vacant Possession (1994) in my personal essay documentary The Silences, as well as clips from other films I had made. Later I reimagined other clips from Vacant Possession in my poetic essay documentary Undercurrents: Meditations on Power – both are screening in Jeonju. This ‘quoting’ from my own body of work, where I own the copyright, has given me the freedom to make low budget experimental work, with high quality images. I have also worked with the archive of Maori artist/choregrapher Victoria Hunt, whom I collaborated with in 2019 to make a short called TAKE. She had videoed creative development workshops, as well as performances, and we had access to archival photographs.

What’s your estimation of the other film in the program, Corinne Cantrill’s In This Life’s Body (1984)? When did you first encounter it? Do you now regard it as an Australian classic?

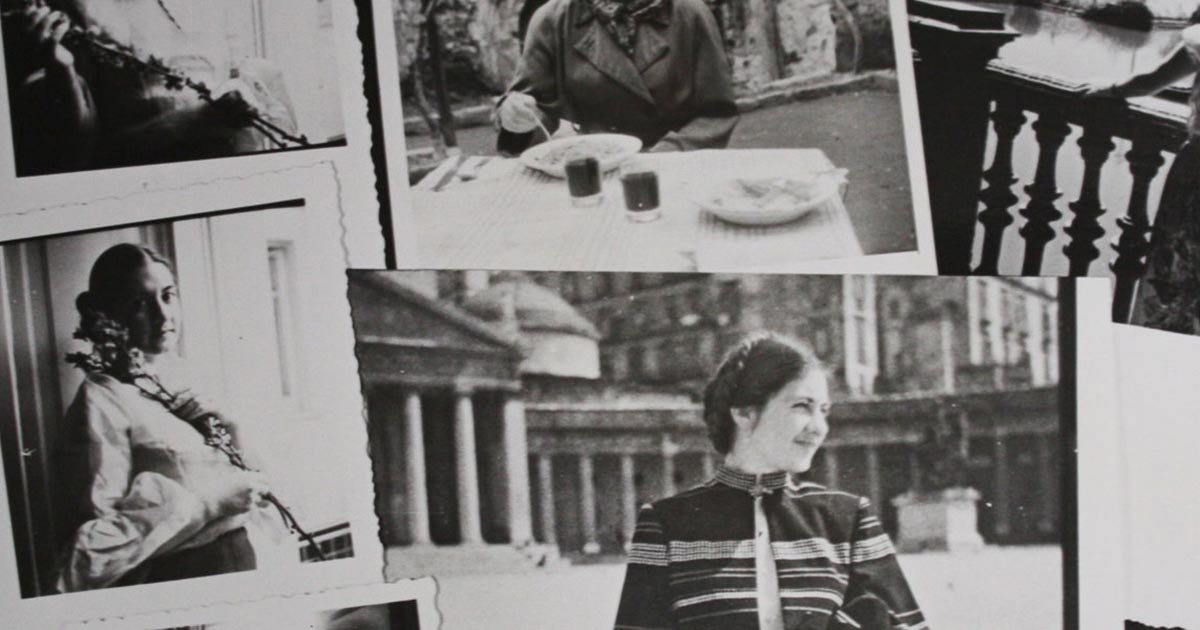

MARGOT I think In This Life’s Body is definitely a classic. I have loved it ever since I first saw it many years ago, with Corinne doing Tai Chi on the stage in front of the image. The combination of live performance with a black and white negative image of Corinne lying naked on a river bank is imprinted in my memory. And the film – so uncompromising and raw – allows us into her personal world as she peels away layers of wounding, longing and desire, searching the known and the unknown. Discovering love, beauty, courage … and film. It was an inspiration to me when I was making The Silences. Her use of mainly still photographs, and her voice, to tell the story is such a rigorous and forensic dive into her personal archive, made when she was facing a cancer diagnosis. When I made The Silences,I too had to explore my personal family archive unflinchingly, and find the courage to speak honestly about the past the way Corinne had. I wrote a critical essay about In This Life’s Body in the journal Senses of Cinema and, when I was teaching, I managed to get Corinne to agree to a digital scan of the film, so I could use it in my alternative Australian film history class. Corinne and her husband Arthur have played a unique role in the history of Australian experimental film, but this film is different to the more formal avant-garde film works they have made. They were film purists and wanted their experimental work to be seen in its original 16mm form, so you are very lucky in Jeonju to be able to see a 16mm print. Corinne would have been pleased. She enjoyed a long and creative life, dying recently aged 96.

BILL In This Life’s Body is an incredible film, no doubt. I’d say it is indeed an Australian classic, along with a number of other alternative features or documentaries (or even shorts or experimental films). As a self-examination, it is thorough and cutting, and its form is magnificently rigorous. I first saw Corinne’s film around the time it was released (mid-1980s), or maybe a few years after that. I have not seen it again, alas, so I wish I was there at Jeonju to watch it again. I hope that the recent focus on the film (in Australia, and elsewhere) due to her recent passing away does not ultimately overshadow the achievements of her work with her husband, Arthur Cantrill. But I don’t think it will, considering the breadth and quantity of their work and legacy.

스털링의 내 사랑 My Darling in Stirling

감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 2023 | 80min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 1983 | 10min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Australia | 2010 | 8min | Experimental | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

감독 빌 머술러스 Bill MOUSOULIS | Greece, Italy, Australia | 2011 | 7min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

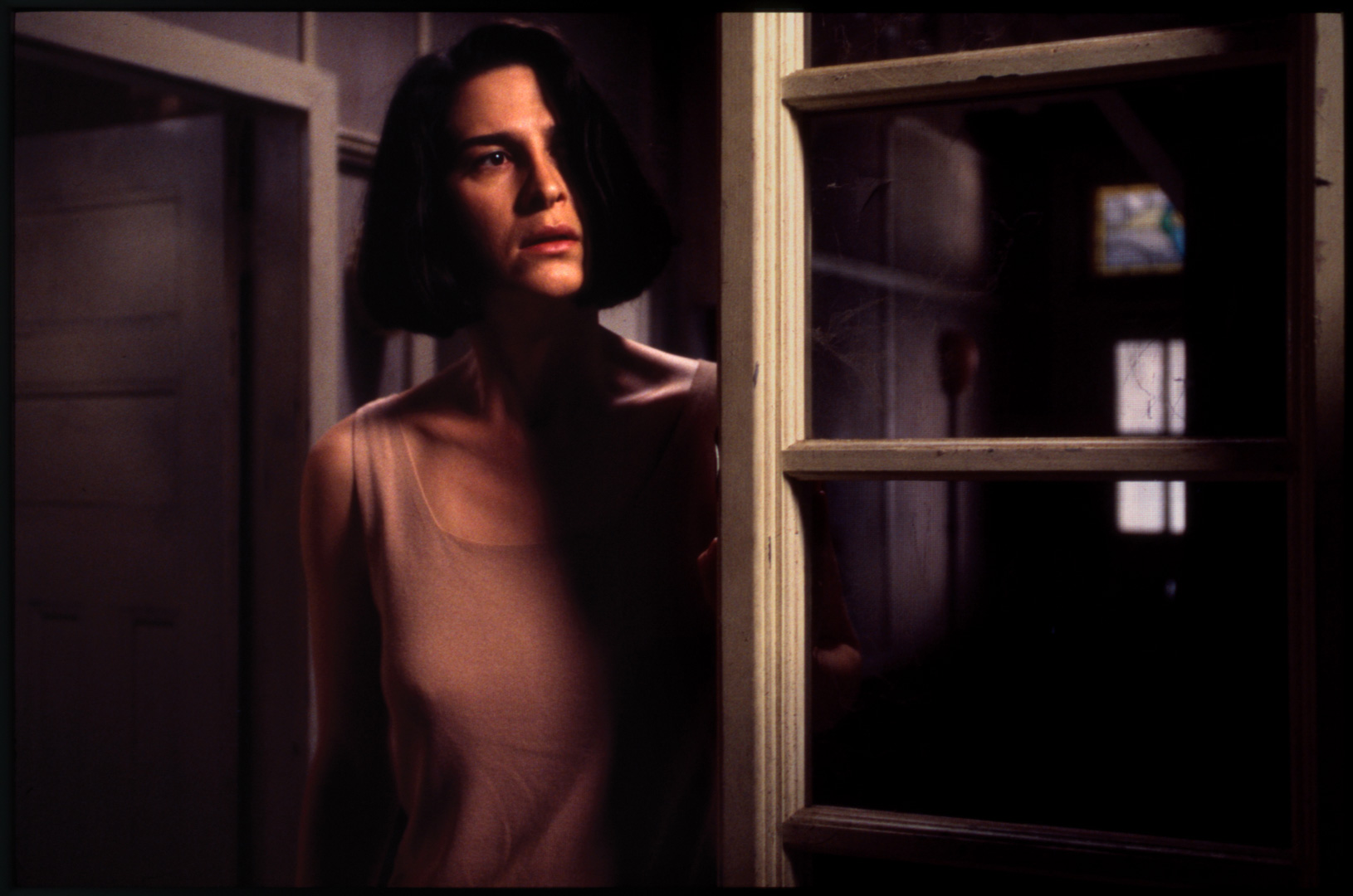

감독 마고 내시 Margot NASH | Australia | 1994 | 95min | Fiction | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

언더커런츠: 힘에 관한 명상 Undercurrents: meditations on power

감독 마고 내시 Margot NASH | Australia | 2023 | 20min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin

감독 커린 캔트릴 Corinne CANTRILL | Australia | 1984 | 147min | Documentary | 게스트 시네필: 에이드리언 마틴 Guest Cinephile: Adrian Martin